Chapter 14 Random variables

In data science, we often deal with data that is affected by chance in some way: the data comes from a random sample, the data is affected by measurement error, or the data measures some outcome that is random in nature. Being able to quantify the uncertainty introduced by randomness is one of the most important jobs of a data analyst. Statistical inference offers a framework, as well as several practical tools, for doing this. The first step is to learn how to mathematically describe random variables.

In this chapter, we introduce random variables and their properties starting with their application to games of chance. We then describe some of the events surrounding the financial crisis of 2007-200847 using probability theory. This financial crisis was in part caused by underestimating the risk of certain securities48 sold by financial institutions. Specifically, the risks of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO) were grossly underestimated. These assets were sold at prices that assumed most homeowners would make their monthly payments, and the probability of this not occurring was calculated as being low. A combination of factors resulted in many more defaults than were expected, which led to a price crash of these securities. As a consequence, banks lost so much money that they needed government bailouts to avoid closing down completely.

14.1 Random variables

Random variables are numeric outcomes resulting from random processes. We can easily generate random variables using some of the simple examples we have shown. For example, define X to be 1 if a bead is blue and red otherwise:

Here X is a random variable: every time we select a new bead the outcome changes randomly. See below:

ifelse(sample(beads, 1) == "blue", 1, 0)

#> [1] 1

ifelse(sample(beads, 1) == "blue", 1, 0)

#> [1] 0

ifelse(sample(beads, 1) == "blue", 1, 0)

#> [1] 0Sometimes it’s 1 and sometimes it’s 0.

14.2 Sampling models

Many data generation procedures, those that produce the data we study, can be modeled quite well as draws from an urn. For instance, we can model the process of polling likely voters as drawing 0s (Republicans) and 1s (Democrats) from an urn containing the 0 and 1 code for all likely voters. In epidemiological studies, we often assume that the subjects in our study are a random sample from the population of interest. The data related to a specific outcome can be modeled as a random sample from an urn containing the outcome for the entire population of interest. Similarly, in experimental research, we often assume that the individual organisms we are studying, for example worms, flies, or mice, are a random sample from a larger population. Randomized experiments can also be modeled by draws from an urn given the way individuals are assigned into groups: when getting assigned, you draw your group at random. Sampling models are therefore ubiquitous in data science. Casino games offer a plethora of examples of real-world situations in which sampling models are used to answer specific questions. We will therefore start with such examples.

Suppose a very small casino hires you to consult on whether they should set up roulette wheels. To keep the example simple, we will assume that 1,000 people will play and that the only game you can play on the roulette wheel is to bet on red or black. The casino wants you to predict how much money they will make or lose. They want a range of values and, in particular, they want to know what’s the chance of losing money. If this probability is too high, they will pass on installing roulette wheels.

We are going to define a random variable \(S\) that will represent the casino’s total winnings. Let’s start by constructing the urn. A roulette wheel has 18 red pockets, 18 black pockets and 2 green ones. So playing a color in one game of roulette is equivalent to drawing from this urn:

The 1,000 outcomes from 1,000 people playing are independent draws from this urn. If red comes up, the gambler wins and the casino loses a dollar, so we draw a -$1. Otherwise, the casino wins a dollar and we draw a $1. To construct our random variable \(S\), we can use this code:

n <- 1000

X <- sample(ifelse(color == "Red", -1, 1), n, replace = TRUE)

X[1:10]

#> [1] -1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 1 1Because we know the proportions of 1s and -1s, we can generate the draws with one line of code, without defining color:

We call this a sampling model since we are modeling the random behavior of roulette with the sampling of draws from an urn. The total winnings \(S\) is simply the sum of these 1,000 independent draws:

14.3 The probability distribution of a random variable

If you run the code above, you see that \(S\) changes every time. This is, of course, because \(S\) is a random variable. The probability distribution of a random variable tells us the probability of the observed value falling at any given interval. So, for example, if we want to know the probability that we lose money, we are asking the probability that \(S\) is in the interval \(S<0\).

Note that if we can define a cumulative distribution function \(F(a) = \mbox{Pr}(S\leq a)\), then we will be able to answer any question related to the probability of events defined by our random variable \(S\), including the event \(S<0\). We call this \(F\) the random variable’s distribution function.

We can estimate the distribution function for the random variable \(S\) by using a Monte Carlo simulation to generate many realizations of the random variable. With this code, we run the experiment of having 1,000 people play roulette, over and over, specifically \(B = 10,000\) times:

n <- 1000

B <- 10000

roulette_winnings <- function(n){

X <- sample(c(-1,1), n, replace = TRUE, prob=c(9/19, 10/19))

sum(X)

}

S <- replicate(B, roulette_winnings(n))Now we can ask the following: in our simulations, how often did we get sums less than or equal to a?

This will be a very good approximation of \(F(a)\) and we can easily answer the casino’s question: how likely is it that we will lose money? We can see it is quite low:

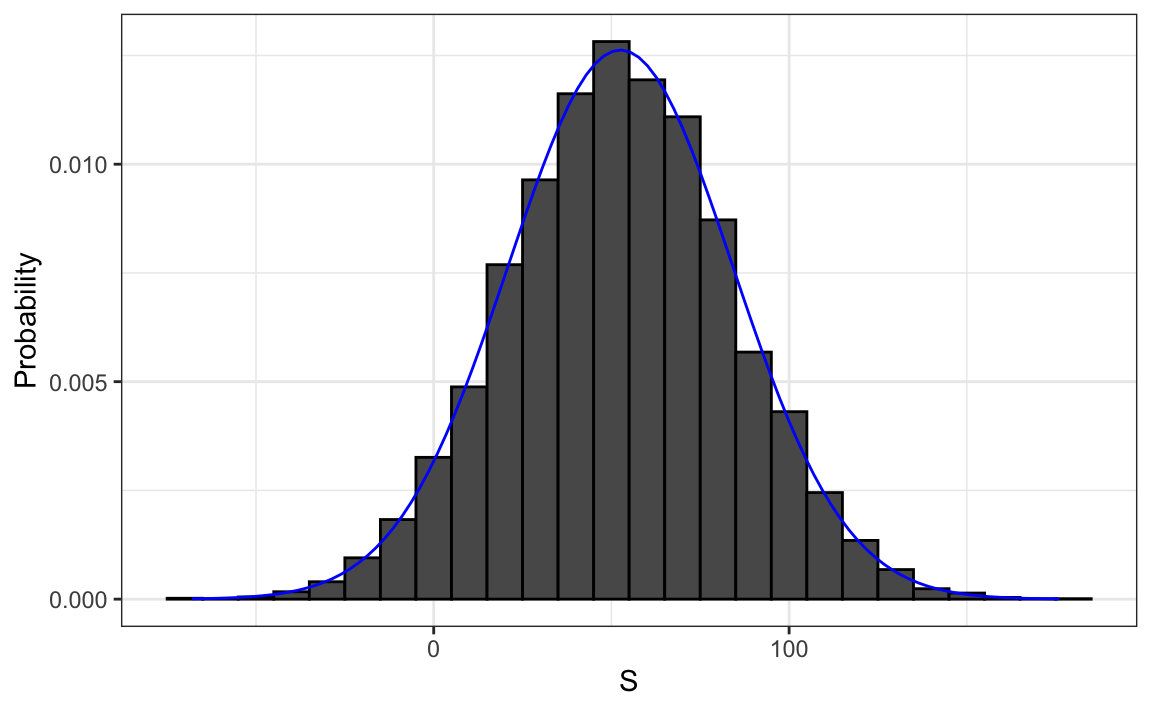

We can visualize the distribution of \(S\) by creating a histogram showing the probability \(F(b)-F(a)\) for several intervals \((a,b]\):

We see that the distribution appears to be approximately normal. A qq-plot will confirm that the normal approximation is close to a perfect approximation for this distribution. If, in fact, the distribution is normal, then all we need to define the distribution is the average and the standard deviation. Because we have the original values from which the distribution is created, we can easily compute these with mean(S) and sd(S). The blue curve you see added to the histogram above is a normal density with this average and standard deviation.

This average and this standard deviation have special names. They are referred to as the expected value and standard error of the random variable \(S\). We will say more about these in the next section.

Statistical theory provides a way to derive the distribution of random variables defined as independent random draws from an urn. Specifically, in our example above, we can show that \((S+n)/2\) follows a binomial distribution. We therefore do not need to run for Monte Carlo simulations to know the probability distribution of \(S\). We did this for illustrative purposes.

We can use the function dbinom and pbinom to compute the probabilities exactly. For example, to compute \(\mbox{Pr}(S < 0)\) we note that:

\[\mbox{Pr}(S < 0) = \mbox{Pr}((S+n)/2 < (0+n)/2)\]

and we can use the pbinom to compute \[\mbox{Pr}(S \leq 0)\]

Because this is a discrete probability function, to get \(\mbox{Pr}(S < 0)\) rather than \(\mbox{Pr}(S \leq 0)\), we write:

For the details of the binomial distribution, you can consult any basic probability book or even Wikipedia49.

Here we do not cover these details. Instead, we will discuss an incredibly useful approximation provided by mathematical theory that applies generally to sums and averages of draws from any urn: the Central Limit Theorem (CLT).

14.4 Distributions versus probability distributions

Before we continue, let’s make an important distinction and connection between the distribution of a list of numbers and a probability distribution. In the visualization chapter, we described how any list of numbers \(x_1,\dots,x_n\) has a distribution. The definition is quite straightforward. We define \(F(a)\) as the function that tells us what proportion of the list is less than or equal to \(a\). Because they are useful summaries when the distribution is approximately normal, we define the average and standard deviation. These are defined with a straightforward operation of the vector containing the list of numbers x:

A random variable \(X\) has a distribution function. To define this, we do not need a list of numbers. It is a theoretical concept. In this case, we define the distribution as the \(F(a)\) that answers the question: what is the probability that \(X\) is less than or equal to \(a\)? There is no list of numbers.

However, if \(X\) is defined by drawing from an urn with numbers in it, then there is a list: the list of numbers inside the urn. In this case, the distribution of that list is the probability distribution of \(X\) and the average and standard deviation of that list are the expected value and standard error of the random variable.

Another way to think about it that does not involve an urn is to run a Monte Carlo simulation and generate a very large list of outcomes of \(X\). These outcomes are a list of numbers. The distribution of this list will be a very good approximation of the probability distribution of \(X\). The longer the list, the better the approximation. The average and standard deviation of this list will approximate the expected value and standard error of the random variable.

14.5 Notation for random variables

In statistical textbooks, upper case letters are used to denote random variables and we follow this convention here. Lower case letters are used for observed values. You will see some notation that includes both. For example, you will see events defined as \(X \leq x\). Here \(X\) is a random variable, making it a random event, and \(x\) is an arbitrary value and not random. So, for example, \(X\) might represent the number on a die roll and \(x\) will represent an actual value we see 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. So in this case, the probability of \(X=x\) is 1/6 regardless of the observed value \(x\). This notation is a bit strange because, when we ask questions about probability, \(X\) is not an observed quantity. Instead, it’s a random quantity that we will see in the future. We can talk about what we expect it to be, what values are probable, but not what it is. But once we have data, we do see a realization of \(X\). So data scientists talk of what could have been after we see what actually happened.

14.6 The expected value and standard error

We have described sampling models for draws. We will now go over the mathematical theory that lets us approximate the probability distributions for the sum of draws. Once we do this, we will be able to help the casino predict how much money they will make. The same approach we use for the sum of draws will be useful for describing the distribution of averages and proportion which we will need to understand how polls work.

The first important concept to learn is the expected value. In statistics books, it is common to use letter \(\mbox{E}\) like this:

\[\mbox{E}[X]\]

to denote the expected value of the random variable \(X\).

A random variable will vary around its expected value in a way that if you take the average of many, many draws, the average of the draws will approximate the expected value, getting closer and closer the more draws you take.

Theoretical statistics provides techniques that facilitate the calculation of expected values in different circumstances. For example, a useful formula tells us that the expected value of a random variable defined by one draw is the average of the numbers in the urn. In the urn used to model betting on red in roulette, we have 20 one dollars and 18 negative one dollars. The expected value is thus:

\[ \mbox{E}[X] = (20 + -18)/38 \]

which is about 5 cents. It is a bit counterintuitive to say that \(X\) varies around 0.05, when the only values it takes is 1 and -1. One way to make sense of the expected value in this context is by realizing that if we play the game over and over, the casino wins, on average, 5 cents per game. A Monte Carlo simulation confirms this:

In general, if the urn has two possible outcomes, say \(a\) and \(b\), with proportions \(p\) and \(1-p\) respectively, the average is:

\[\mbox{E}[X] = ap + b(1-p)\]

To see this, notice that if there are \(n\) beads in the urn, then we have \(np\) \(a\)s and \(n(1-p)\) \(b\)s and because the average is the sum, \(n\times a \times p + n\times b \times (1-p)\), divided by the total \(n\), we get that the average is \(ap + b(1-p)\).

Now the reason we define the expected value is because this mathematical definition turns out to be useful for approximating the probability distributions of sum, which then is useful for describing the distribution of averages and proportions. The first useful fact is that the expected value of the sum of the draws is:

\[ \mbox{}\mbox{number of draws } \times \mbox{ average of the numbers in the urn} \]

So if 1,000 people play roulette, the casino expects to win, on average, about 1,000 \(\times\) $0.05 = $50. But this is an expected value. How different can one observation be from the expected value? The casino really needs to know this. What is the range of possibilities? If negative numbers are too likely, they will not install roulette wheels. Statistical theory once again answers this question. The standard error (SE) gives us an idea of the size of the variation around the expected value. In statistics books, it’s common to use:

\[\mbox{SE}[X]\]

to denote the standard error of a random variable.

If our draws are independent, then the standard error of the sum is given by the equation:

\[ \sqrt{\mbox{number of draws }} \times \mbox{ standard deviation of the numbers in the urn} \]

Using the definition of standard deviation, we can derive, with a bit of math, that if an urn contains two values \(a\) and \(b\) with proportions \(p\) and \((1-p)\), respectively, the standard deviation is:

\[\mid b - a \mid \sqrt{p(1-p)}.\]

So in our roulette example, the standard deviation of the values inside the urn is: \(\mid 1 - (-1) \mid \sqrt{10/19 \times 9/19}\) or:

The standard error tells us the typical difference between a random variable and its expectation. Since one draw is obviously the sum of just one draw, we can use the formula above to calculate that the random variable defined by one draw has an expected value of 0.05 and a standard error of about 1. This makes sense since we either get 1 or -1, with 1 slightly favored over -1.

Using the formula above, the sum of 1,000 people playing has standard error of about $32:

As a result, when 1,000 people bet on red, the casino is expected to win $50 with a standard error of $32. It therefore seems like a safe bet. But we still haven’t answered the question: how likely is it to lose money? Here the CLT will help.

Advanced note: Before continuing we should point out that exact probability calculations for the casino winnings can be performed with the binomial distribution. However, here we focus on the CLT, which can be generally applied to sums of random variables in a way that the binomial distribution can’t.

14.6.1 Population SD versus the sample SD

The standard deviation of a list x (below we use heights as an example) is defined as the square root of the average of the squared differences:

Using mathematical notation we write:

\[ \mu = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \\ \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu)^2} \]

However, be aware that the sd function returns a slightly different result:

This is because the sd function R does not return the sd of the list, but rather uses a formula that estimates standard deviations of a population from a random sample \(X_1, \dots, X_N\) which, for reasons not discussed here, divide the sum of squares by the \(N-1\).

\[ \bar{X} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N X_i, \,\,\,\, s = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N-1} \sum_{i=1}^N (X_i - \bar{X})^2} \]

You can see that this is the case by typing:

For all the theory discussed here, you need to compute the actual standard deviation as defined:

So be careful when using the sd function in R. However, keep in mind that throughout the book we sometimes use the sd function when we really want the actual SD. This is because when the list size is big, these two are practically equivalent since \(\sqrt{(N-1)/N} \approx 1\).

14.7 Central Limit Theorem

The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) tells us that when the number of draws, also called the sample size, is large, the probability distribution of the sum of the independent draws is approximately normal. Because sampling models are used for so many data generation processes, the CLT is considered one of the most important mathematical insights in history.

Previously, we discussed that if we know that the distribution of a list of numbers is approximated by the normal distribution, all we need to describe the list are the average and standard deviation. We also know that the same applies to probability distributions. If a random variable has a probability distribution that is approximated with the normal distribution, then all we need to describe the probability distribution are the average and standard deviation, referred to as the expected value and standard error.

We previously ran this Monte Carlo simulation:

n <- 1000

B <- 10000

roulette_winnings <- function(n){

X <- sample(c(-1,1), n, replace = TRUE, prob=c(9/19, 10/19))

sum(X)

}

S <- replicate(B, roulette_winnings(n))The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) tells us that the sum \(S\) is approximated by a normal distribution. Using the formulas above, we know that the expected value and standard error are:

The theoretical values above match those obtained with the Monte Carlo simulation:

Using the CLT, we can skip the Monte Carlo simulation and instead compute the probability of the casino losing money using this approximation:

which is also in very good agreement with our Monte Carlo result:

14.7.1 How large is large in the Central Limit Theorem?

The CLT works when the number of draws is large. But large is a relative term. In many circumstances as few as 30 draws is enough to make the CLT useful. In some specific instances, as few as 10 is enough. However, these should not be considered general rules. Note, for example, that when the probability of success is very small, we need much larger sample sizes.

By way of illustration, let’s consider the lottery. In the lottery, the chances of winning are less than 1 in a million. Thousands of people play so the number of draws is very large. Yet the number of winners, the sum of the draws, range between 0 and 4. This sum is certainly not well approximated by a normal distribution, so the CLT does not apply, even with the very large sample size. This is generally true when the probability of a success is very low. In these cases, the Poisson distribution is more appropriate.

You can examine the properties of the Poisson distribution using dpois and ppois. You can generate random variables following this distribution with rpois. However, we do not cover the theory here. You can learn about the Poisson distribution in any probability textbook and even Wikipedia50

14.8 Statistical properties of averages

There are several useful mathematical results that we used above and often employ when working with data. We list them below.

1. The expected value of the sum of random variables is the sum of each random variable’s expected value. We can write it like this:

\[ \mbox{E}[X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n] = \mbox{E}[X_1] + \mbox{E}[X_2]+\dots+\mbox{E}[X_n] \]

If the \(X\) are independent draws from the urn, then they all have the same expected value. Let’s call it \(\mu\) and thus:

\[ \mbox{E}[X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n]= n\mu \]

which is another way of writing the result we show above for the sum of draws.

2. The expected value of a non-random constant times a random variable is the non-random constant times the expected value of a random variable. This is easier to explain with symbols:

\[ \mbox{E}[aX] = a\times\mbox{E}[X] \]

To see why this is intuitive, consider change of units. If we change the units of a random variable, say from dollars to cents, the expectation should change in the same way. A consequence of the above two facts is that the expected value of the average of independent draws from the same urn is the expected value of the urn, call it \(\mu\) again:

\[ \mbox{E}[(X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n) / n]= \mbox{E}[X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n] / n = n\mu/n = \mu \]

3. The square of the standard error of the sum of independent random variables is the sum of the square of the standard error of each random variable. This one is easier to understand in math form:

\[ \mbox{SE}[X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n] = \sqrt{\mbox{SE}[X_1]^2 + \mbox{SE}[X_2]^2+\dots+\mbox{SE}[X_n]^2 } \]

The square of the standard error is referred to as the variance in statistical textbooks. Note that this particular property is not as intuitive as the previous three and more in depth explanations can be found in statistics textbooks.

4. The standard error of a non-random constant times a random variable is the non-random constant times the random variable’s standard error. As with the expectation: \[ \mbox{SE}[aX] = a \times \mbox{SE}[X] \]

To see why this is intuitive, again think of units.

A consequence of 3 and 4 is that the standard error of the average of independent draws from the same urn is the standard deviation of the urn divided by the square root of \(n\) (the number of draws), call it \(\sigma\):

\[ \begin{aligned} \mbox{SE}[(X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n) / n] &= \mbox{SE}[X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n]/n \\ &= \sqrt{\mbox{SE}[X_1]^2+\mbox{SE}[X_2]^2+\dots+\mbox{SE}[X_n]^2}/n \\ &= \sqrt{\sigma^2+\sigma^2+\dots+\sigma^2}/n\\ &= \sqrt{n\sigma^2}/n\\ &= \sigma / \sqrt{n} \end{aligned} \]

5. If \(X\) is a normally distributed random variable, then if \(a\) and \(b\) are non-random constants, \(aX + b\) is also a normally distributed random variable. All we are doing is changing the units of the random variable by multiplying by \(a\), then shifting the center by \(b\).

Note that statistical textbooks use the Greek letters \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) to denote the expected value and standard error, respectively. This is because \(\mu\) is the Greek letter for \(m\), the first letter of mean, which is another term used for expected value. Similarly, \(\sigma\) is the Greek letter for \(s\), the first letter of standard error.

14.9 Law of large numbers

An important implication of the final result is that the standard error of the average becomes smaller and smaller as \(n\) grows larger. When \(n\) is very large, then the standard error is practically 0 and the average of the draws converges to the average of the urn. This is known in statistical textbooks as the law of large numbers or the law of averages.

14.9.1 Misinterpreting law of averages

The law of averages is sometimes misinterpreted. For example, if you toss a coin 5 times and see a head each time, you might hear someone argue that the next toss is probably a tail because of the law of averages: on average we should see 50% heads and 50% tails. A similar argument would be to say that red “is due” on the roulette wheel after seeing black come up five times in a row. These events are independent so the chance of a coin landing heads is 50% regardless of the previous 5. This is also the case for the roulette outcome. The law of averages applies only when the number of draws is very large and not in small samples. After a million tosses, you will definitely see about 50% heads regardless of the outcome of the first five tosses.

Another funny misuse of the law of averages is in sports when TV sportscasters predict a player is about to succeed because they have failed a few times in a row.

14.10 Exercises

1. In American Roulette you can also bet on green. There are 18 reds, 18 blacks and 2 greens (0 and 00). What are the chances the green comes out?

2. The payout for winning on green is $17 dollars. This means that if you bet a dollar and it lands on green, you get $17. Create a sampling model using sample to simulate the random variable \(X\) for your winnings. Hint: see the example below for how it should look like when betting on red.

3. Compute the expected value of \(X\).

4. Compute the standard error of \(X\).

5. Now create a random variable \(S\) that is the sum of your winnings after betting on green 1000 times. Hint: change the argument size and replace in your answer to question 2. Start your code by setting the seed to 1 with set.seed(1).

6. What is the expected value of \(S\)?

7. What is the standard error of \(S\)?

8. What is the probability that you end up winning money? Hint: use the CLT.

9. Create a Monte Carlo simulation that generates 1,000 outcomes of \(S\). Compute the average and standard deviation of the resulting list to confirm the results of 6 and 7. Start your code by setting the seed to 1 with set.seed(1).

10. Now check your answer to 8 using the Monte Carlo result.

11. The Monte Carlo result and the CLT approximation are close, but not that close. What could account for this?

- 1,000 simulations is not enough. If we do more, they match.

- The CLT does not work as well when the probability of success is small. In this case, it was 1/19. If we make the number of roulette plays bigger, they will match better.

- The difference is within rounding error.

- The CLT only works for averages.

12. Now create a random variable \(Y\) that is your average winnings per bet after playing off your winnings after betting on green 1,000 times.

13. What is the expected value of \(Y\)?

14. What is the standard error of \(Y\)?

15. What is the probability that you end up with winnings per game that are positive? Hint: use the CLT.

16. Create a Monte Carlo simulation that generates 2,500 outcomes of \(Y\). Compute the average and standard deviation of the resulting list to confirm the results of 6 and 7. Start your code by setting the seed to 1 with set.seed(1).

17. Now check your answer to 8 using the Monte Carlo result.

18. The Monte Carlo result and the CLT approximation are now much closer. What could account for this?

- We are now computing averages instead of sums.

- 2,500 Monte Carlo simulations is not better than 1,000.

- The CLT works better when the sample size is larger. We increased from 1,000 to 2,500.

- It is not closer. The difference is within rounding error.

14.11 Case study: The Big Short

14.11.1 Interest rates explained with chance model

More complex versions of the sampling models we have discussed are also used by banks to decide interest rates. Suppose you run a small bank that has a history of identifying potential homeowners that can be trusted to make payments. In fact, historically, in a given year, only 2% of your customers default, meaning that they don’t pay back the money that you lent them. However, you are aware that if you simply loan money to everybody without interest, you will end up losing money due to this 2%. Although you know 2% of your clients will probably default, you don’t know which ones. Yet by charging everybody just a bit extra in interest, you can make up the losses incurred due to that 2% and also cover your operating costs. You can also make a profit, but if you set the interest rates too high, your clients will go to another bank. We use all these facts and some probability theory to decide what interest rate you should charge.

Suppose your bank will give out 1,000 loans for $180,000 this year. Also, after adding up all costs, suppose your bank loses $200,000 per foreclosure. For simplicity, we assume this includes all operational costs. A sampling model for this scenario can be coded like this:

n <- 1000

loss_per_foreclosure <- -200000

p <- 0.02

defaults <- sample( c(0,1), n, prob=c(1-p, p), replace = TRUE)

sum(defaults * loss_per_foreclosure)

#> [1] -3600000Note that the total loss defined by the final sum is a random variable. Every time you run the above code, you get a different answer. We can easily construct a Monte Carlo simulation to get an idea of the distribution of this random variable.

B <- 10000

losses <- replicate(B, {

defaults <- sample( c(0,1), n, prob=c(1-p, p), replace = TRUE)

sum(defaults * loss_per_foreclosure)

})We don’t really need a Monte Carlo simulation though. Using what we have learned, the CLT tells us that because our losses are a sum of independent draws, its distribution is approximately normal with expected value and standard errors given by:

n*(p*loss_per_foreclosure + (1-p)*0)

#> [1] -4e+06

sqrt(n)*abs(loss_per_foreclosure)*sqrt(p*(1-p))

#> [1] 885438We can now set an interest rate to guarantee that, on average, we break even. Basically, we need to add a quantity \(x\) to each loan, which in this case are represented by draws, so that the expected value is 0. If we define \(l\) to be the loss per foreclosure, we need:

\[ lp + x(1-p) = 0 \]

which implies \(x\) is

or an interest rate of 0.023.

However, we still have a problem. Although this interest rate guarantees that on average we break even, there is a 50% chance that we lose money. If our bank loses money, we have to close it down. We therefore need to pick an interest rate that makes it unlikely for this to happen. At the same time, if the interest rate is too high, our clients will go to another bank so we must be willing to take some risks. So let’s say that we want our chances of losing money to be 1 in 100, what does the \(x\) quantity need to be now? This one is a bit harder. We want the sum \(S\) to have:

\[\mbox{Pr}(S<0) = 0.01\]

We know that \(S\) is approximately normal. The expected value of \(S\) is

\[\mbox{E}[S] = \{ lp + x(1-p)\}n\]

with \(n\) the number of draws, which in this case represents loans. The standard error is

\[\mbox{SD}[S] = |x-l| \sqrt{np(1-p)}.\]

Because \(x\) is positive and \(l\) negative \(|x-l|=x-l\). Note that these are just an application of the formulas shown earlier, but using more compact symbols.

Now we are going to use a mathematical “trick” that is very common in statistics. We add and subtract the same quantities to both sides of the event \(S<0\) so that the probability does not change and we end up with a standard normal random variable on the left, which will then permit us to write down an equation with only \(x\) as an unknown. This “trick” is as follows:

If \(\mbox{Pr}(S<0) = 0.01\) then \[ \mbox{Pr}\left(\frac{S - \mbox{E}[S]}{\mbox{SE}[S]} < \frac{ - \mbox{E}[S]}{\mbox{SE}[S]}\right) \] And remember \(\mbox{E}[S]\) and \(\mbox{SE}[S]\) are the expected value and standard error of \(S\), respectively. All we did above was add and divide by the same quantity on both sides. We did this because now the term on the left is a standard normal random variable, which we will rename \(Z\). Now we fill in the blanks with the actual formula for expected value and standard error:

\[ \mbox{Pr}\left(Z < \frac{- \{ lp + x(1-p)\}n}{(x-l) \sqrt{np(1-p)}}\right) = 0.01 \]

It may look complicated, but remember that \(l\), \(p\) and \(n\) are all known amounts, so eventually we will replace them with numbers.

Now because the Z is a normal random with expected value 0 and standard error 1, it means that the quantity on the right side of the < sign must be equal to:

for the equation to hold true. Remember that \(z=\)qnorm(0.01) gives us the value of \(z\) for which:

\[ \mbox{Pr}(Z \leq z) = 0.01 \]

So this means that the right side of the complicated equation must be \(z\)=qnorm(0.01).

\[ \frac{- \{ lp + x(1-p)\}n} {(x-l) \sqrt{n p (1-p)}} = z \]

The trick works because we end up with an expression containing \(x\) that we know has to be equal to a known quantity \(z\). Solving for \(x\) is now simply algebra:

\[ x = - l \frac{ np - z \sqrt{np(1-p)}}{n(1-p) + z \sqrt{np(1-p)}}\]

which is:

l <- loss_per_foreclosure

z <- qnorm(0.01)

x <- -l*( n*p - z*sqrt(n*p*(1-p)))/ ( n*(1-p) + z*sqrt(n*p*(1-p)))

x

#> [1] 6249Our interest rate now goes up to 0.035. This is still a very competitive interest rate. By choosing this interest rate, we now have an expected profit per loan of:

which is a total expected profit of about:

dollars!

We can run a Monte Carlo simulation to double check our theoretical approximations:

14.11.2 The Big Short

One of your employees points out that since the bank is making 2,124 dollars per loan, the bank should give out more loans! Why just \(n\)? You explain that finding those \(n\) clients was hard. You need a group that is predictable and that keeps the chances of defaults low. He then points out that even if the probability of default is higher, as long as our expected value is positive, you can minimize your chances of losses by increasing \(n\) and relying on the law of large numbers.

He claims that even if the default rate is twice as high, say 4%, if we set the rate just a bit higher than this value:

we will profit. At 5%, we are guaranteed a positive expected value of:

and can minimize our chances of losing money by simply increasing \(n\) since:

\[

\mbox{Pr}(S < 0) =

\mbox{Pr}\left(Z < - \frac{\mbox{E}[S]}{\mbox{SE}[S]}\right)

\]

with \(Z\) a standard normal random variable as shown earlier. If we define \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) to be the expected value and standard deviation of the urn, respectively (that is of a single loan), using the formulas above we have: \(\mbox{E}[S]= n\mu\) and \(\mbox{SE}[S]= \sqrt{n}\sigma\). So if we define \(z\)=qnorm(0.01), we have:

\[

- \frac{n\mu}{\sqrt{n}\sigma} = - \frac{\sqrt{n}\mu}{\sigma} = z

\]

which implies that if we let:

\[ n \geq z^2 \sigma^2 / \mu^2 \] we are guaranteed to have a probability of less than 0.01. The implication is that, as long as \(\mu\) is positive, we can find an \(n\) that minimizes the probability of a loss. This is a form of the law of large numbers: when \(n\) is large, our average earnings per loan converges to the expected earning \(\mu\).

With \(x\) fixed, now we can ask what \(n\) do we need for the probability to be 0.01? In our example, if we give out:

loans, the probability of losing is about 0.01 and we are expected to earn a total of

dollars! We can confirm this with a Monte Carlo simulation:

p <- 0.04

x <- 0.05*180000

profit <- replicate(B, {

draws <- sample( c(x, loss_per_foreclosure), n,

prob=c(1-p, p), replace = TRUE)

sum(draws)

})

mean(profit)

#> [1] 14190724This seems like a no brainer. As a result, your colleague decides to leave your bank and start his own high-risk mortgage company. A few months later, your colleague’s bank has gone bankrupt. A book is written and eventually a movie is made relating the mistake your friend, and many others, made. What happened?

Your colleague’s scheme was mainly based on this mathematical formula: \[ \mbox{SE}[(X_1+X_2+\dots+X_n) / n] = \sigma / \sqrt{n} \]

By making \(n\) large, we minimize the standard error of our per-loan profit. However, for this rule to hold, the \(X\)s must be independent draws: one person defaulting must be independent of others defaulting. Note that in the case of averaging the same event over and over, an extreme example of events that are not independent, we get a standard error that is \(\sqrt{n}\) times bigger: \[ \mbox{SE}[(X_1+X_1+\dots+X_1) / n] = \mbox{SE}[n X_1 / n] = \sigma > \sigma / \sqrt{n} \]

To construct a more realistic simulation than the original one your colleague ran, let’s assume there is a global event that affects everybody with high-risk mortgages and changes their probability. We will assume that with 50-50 chance, all the probabilities go up or down slightly to somewhere between 0.03 and 0.05. But it happens to everybody at once, not just one person. These draws are no longer independent.

p <- 0.04

x <- 0.05*180000

profit <- replicate(B, {

new_p <- 0.04 + sample(seq(-0.01, 0.01, length = 100), 1)

draws <- sample( c(x, loss_per_foreclosure), n,

prob=c(1-new_p, new_p), replace = TRUE)

sum(draws)

})Note that our expected profit is still large:

However, the probability of the bank having negative earnings shoots up to:

Even scarier is that the probability of losing more than 10 million dollars is:

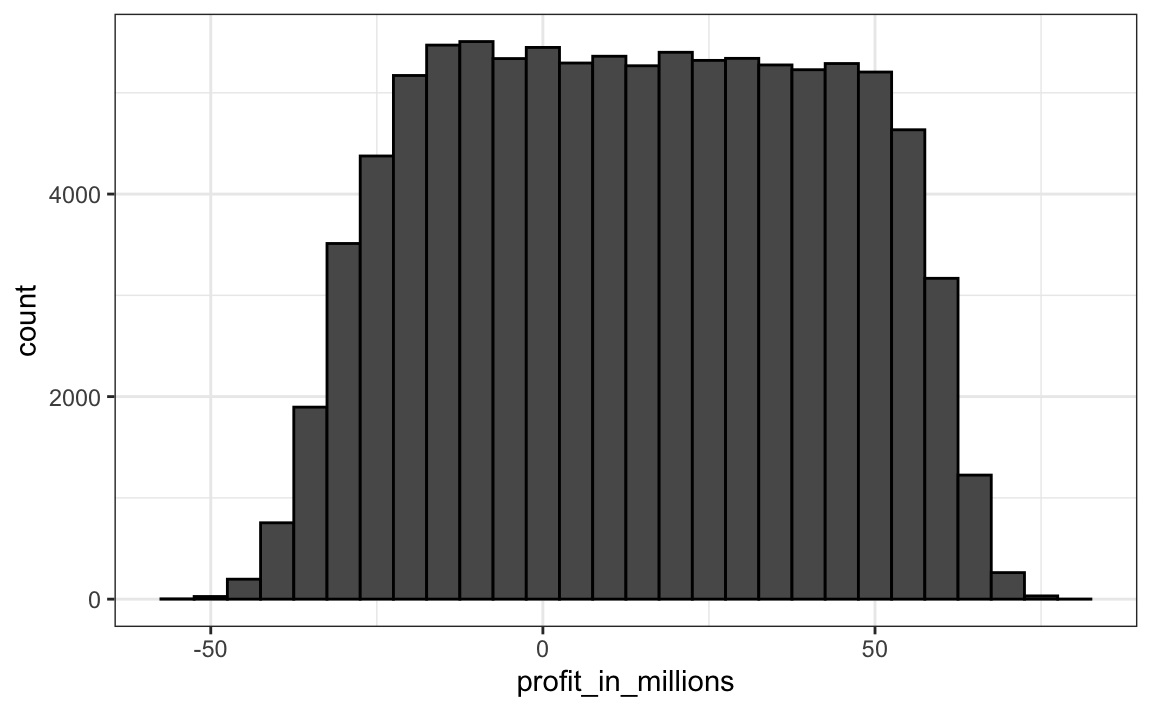

To understand how this happens look at the distribution:

data.frame(profit_in_millions=profit/10^6) |>

ggplot(aes(profit_in_millions)) +

geom_histogram(color="black", binwidth = 5)

The theory completely breaks down and the random variable has much more variability than expected. The financial meltdown of 2007 was due, among other things, to financial “experts” assuming independence when there was none.

14.12 Exercises

1. Create a random variable \(S\) with the earnings of your bank if you give out 10,000 loans, the default rate is 0.3, and you lose $200,000 in each foreclosure. Hint: use the code we showed in the previous section, but change the parameters.

2. Run a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 outcomes for \(S\). Make a histogram of the results.

3. What is the expected value of \(S\)?

4. What is the standard error of \(S\)?

5. Suppose we give out loans for $180,000. What should the interest rate be so that our expected value is 0?

6. (Harder) What should the interest rate be so that the chance of losing money is 1 in 20? In math notation, what should the interest rate be so that \(\mbox{Pr}(S<0) = 0.05\) ?

7. If the bank wants to minimize the probabilities of losing money, which of the following does not make interest rates go up?

- A smaller pool of loans.

- A larger probability of default.

- A smaller required probability of losing money.

- The number of Monte Carlo simulations.