rm *.html18 Organizing with Unix

Unix is the operating system of choice in data science. We will introduce you to the Unix way of thinking using an example: how to keep a data analysis project organized. We will learn some of the most commonly used commands along the way. However, we won’t go into advanced details. We highly encourage you to learn more, especially when you find yourself using the mouse or performing a repetitive task often. In those cases, there is probably a more efficient way to do it in Unix. Here are some basic courses to get you started:

- “Learn the Command Line” through codecademy1

- “LinuxFoundationX: Introduction to Linux” through edX2

- “The Unix Workbench” through coursera3

There are many reference books4 as well. Bite Size Linux5 and Bite Size Command Line6 are two particularly clear, succinct, and complete examples.

When searching for Unix resources, keep in mind that other terms used to describe what we will learn here are Linux, the shell, and the command line. Basically, what we are learning is a series of commands and a way of thinking that facilitates the organization of files without using the mouse.

To serve as motivation, we are going to start constructing a directory using Unix tools and RStudio.

18.1 Naming convention

Before you start organizing projects with Unix you want to pick a name convention that you will use to systematically name your files and directories. This will help you find files and know what is in them.

In general you want to name your files in a way that is related to their contents and specifies how they relate to other files. The Smithsonian Data Management Best Practices7 has “five precepts of file naming and organization” and they are:

- Have a distinctive, human-readable name that gives an indication of the content.

- Follow a consistent pattern that is machine-friendly.

- Organize files into directories (when necessary) that follow a consistent pattern.

- Avoid repetition of semantic elements among file and directory names.

- Have a file extension that matches the file format (no changing extensions!)

For specific recommendations we highly recommend you follow The Tidyverse Style Guide8.

18.2 The terminal

Instead of clicking, dragging, and dropping to organize our files and folders, we will be typing Unix commands into the terminal. The way we do this is similar to how we type commands into the R console, but instead of generating plots and statistical summaries, we will be organizing files on our system.

The terminal is integrated into Mac and Linux systems, but Windows users will have to install an emulator. Once you have a terminal open, you can start typing commands. You should see a blinking cursor at the spot where what you type will show up. This position is called the command line. Once you type something and hit enter on Windows or return on the Mac, Unix will try to execute this command. If you want to try out an example, type this command:

echo "hello world"The command echo is similar to cat in R. Executing this line should print out hello world, then return back to the command line.

Notice that you can’t use the mouse to move around in the terminal. You have to use the keyboard. To go back to a command you previously typed, you can use the up arrow.

Note that above we included a chunk of code showing Unix commands in the same way we have previously shown R commands. We will make sure to distinguish when the command is meant for R and when it is meant for Unix.

18.3 The filesystem

We refer to all the files, folders, and programs on your computer as the filesystem. Keep in mind that folders and programs are also files, but this is a technicality we rarely think about and ignore in this book. We will focus on files and folders for now and discuss programs, or executables, in a later section.

18.3.1 Directories and subdirectories

The first concept you need to grasp to become a Unix user is how your filesystem is organized. You should think of it as a series of nested folders, each containing files, folders, and executables.

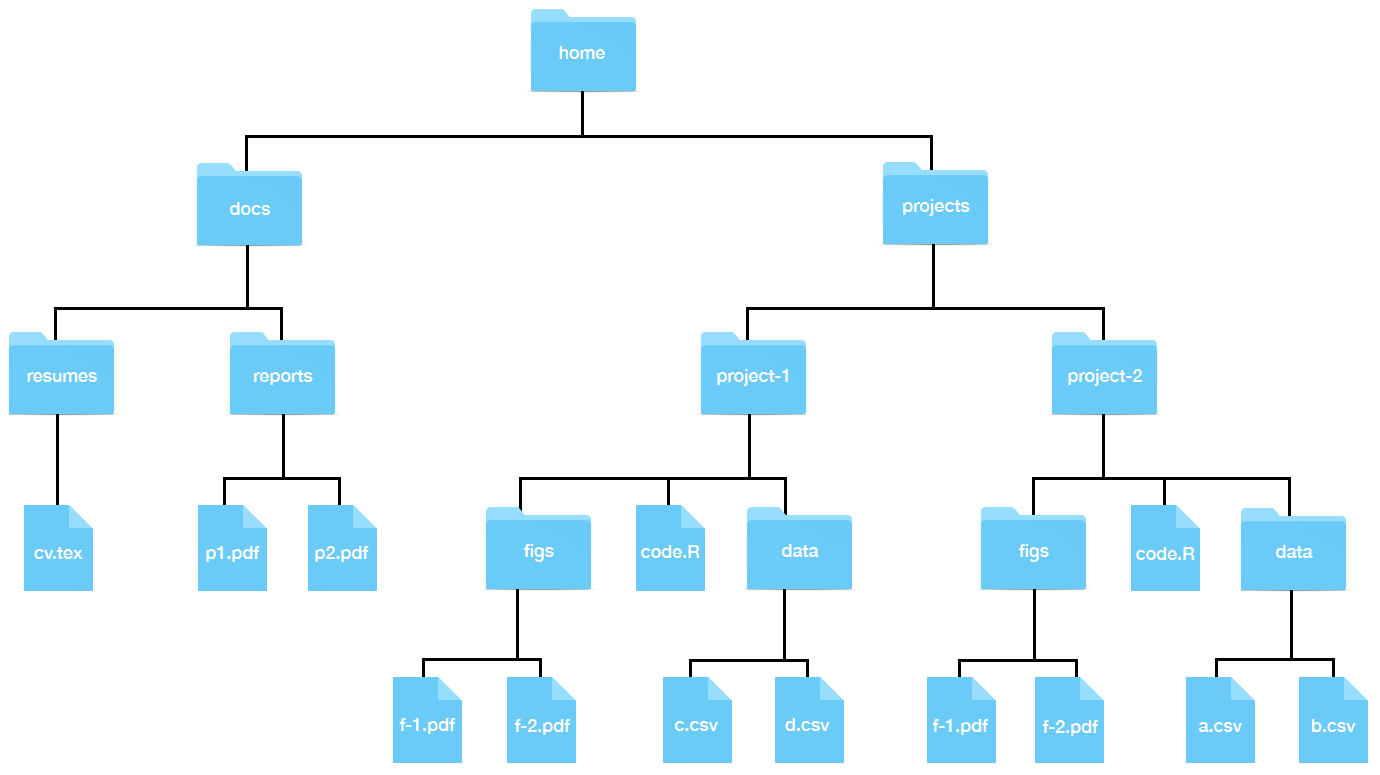

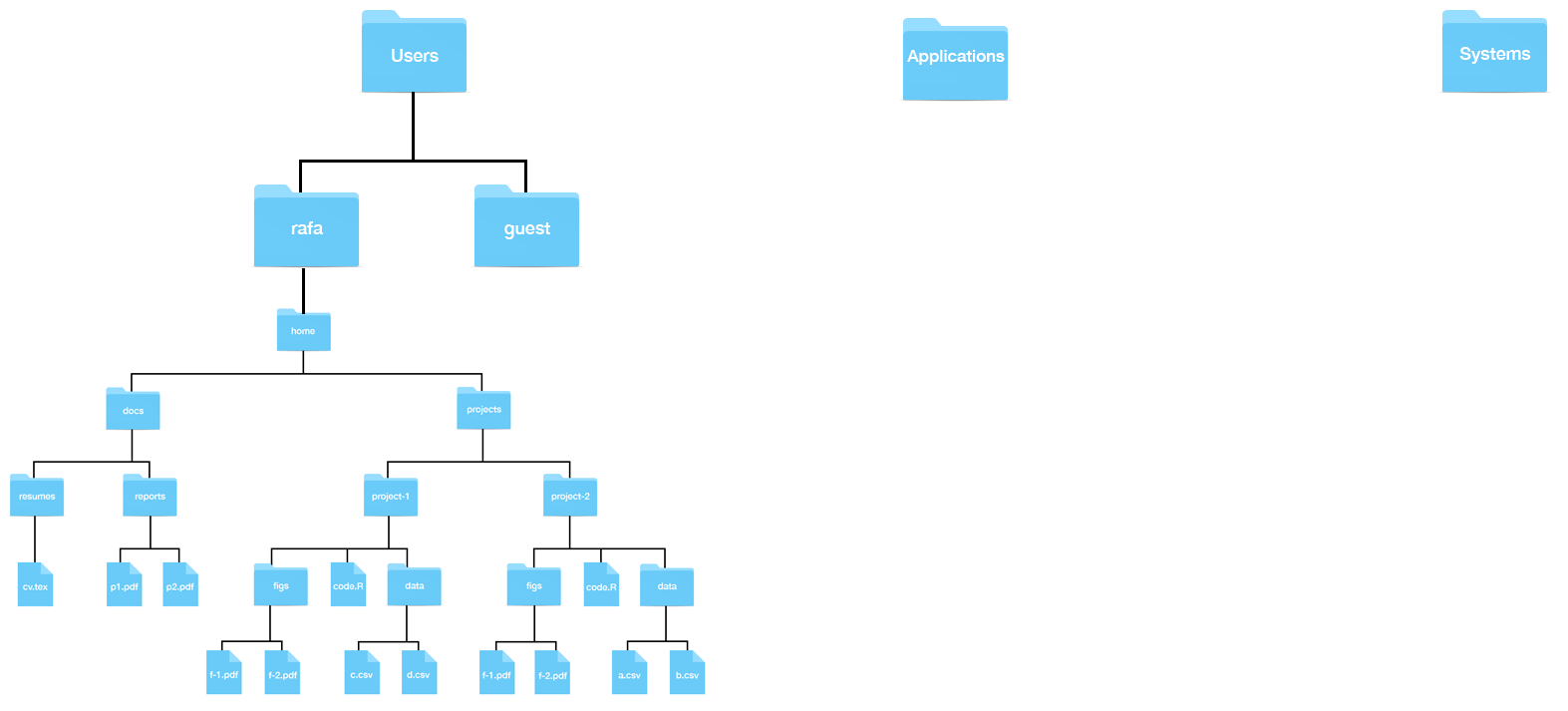

Here is a visual representation of the structure we are describing:

In Unix, we refer to folders as directories. Directories that are inside other directories are often referred to as subdirectories. So, for example, in the figure above, the directory docs has two subdirectories: reports and resumes, and docs is a subdirectory of home.

18.3.2 The home directory

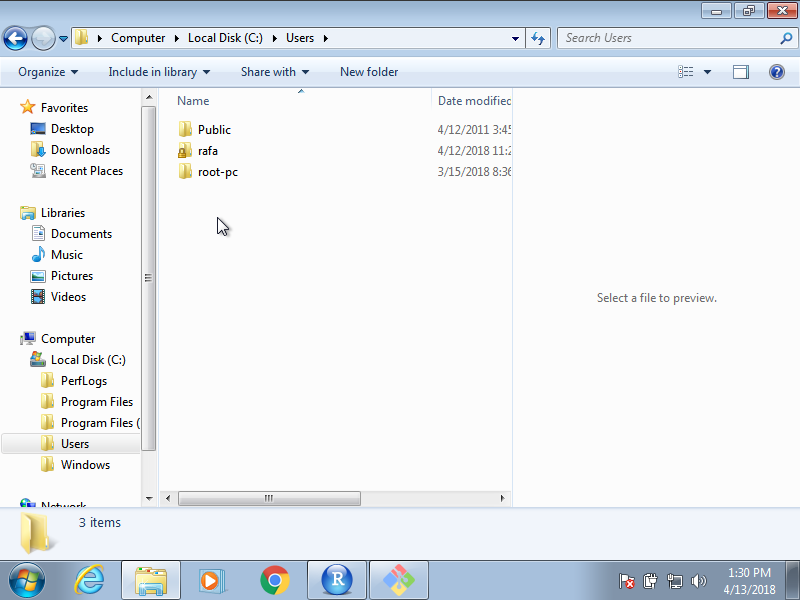

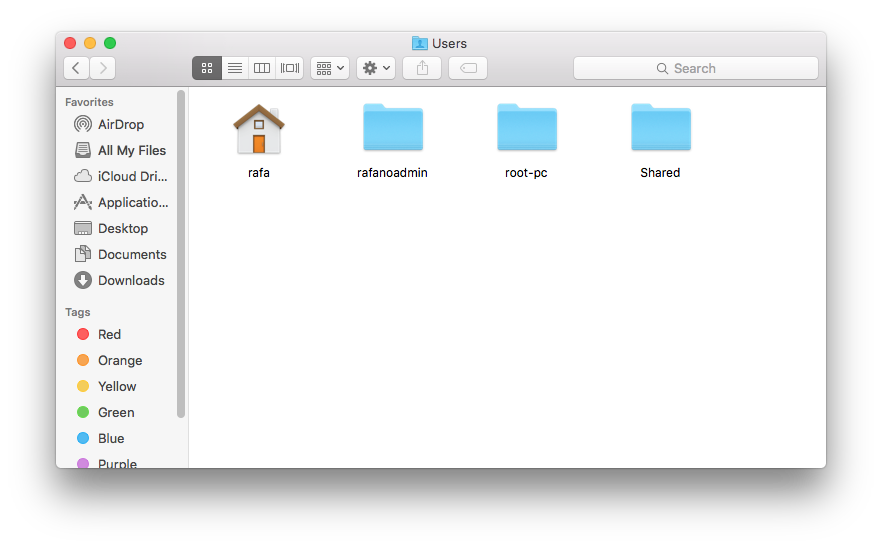

The home directory is where all your stuff is kept, as opposed to the system files that come with your computer, which are kept elsewhere. In the figure above, the directory called home represents your home directory, but that is rarely the name used. On your system, the name of your home directory is likely the same as your username on that system. Below are an example on Windows and Mac showing a home directory, in this case, named rafa:

Now, look back at the figure showing a filesystem. Suppose you are using a point-and-click system and you want to remove the file cv.tex. Imagine that on your screen you can see the home directory. To erase this file, you would double click on the home directory, then docs, then resumes, and then drag cv.tex to the trash. Here you are experiencing the hierarchical nature of the system: cv.tex is a file inside the resumes directory, which is a subdirectory inside the docs directory, which is a subdirectory of the home directory.

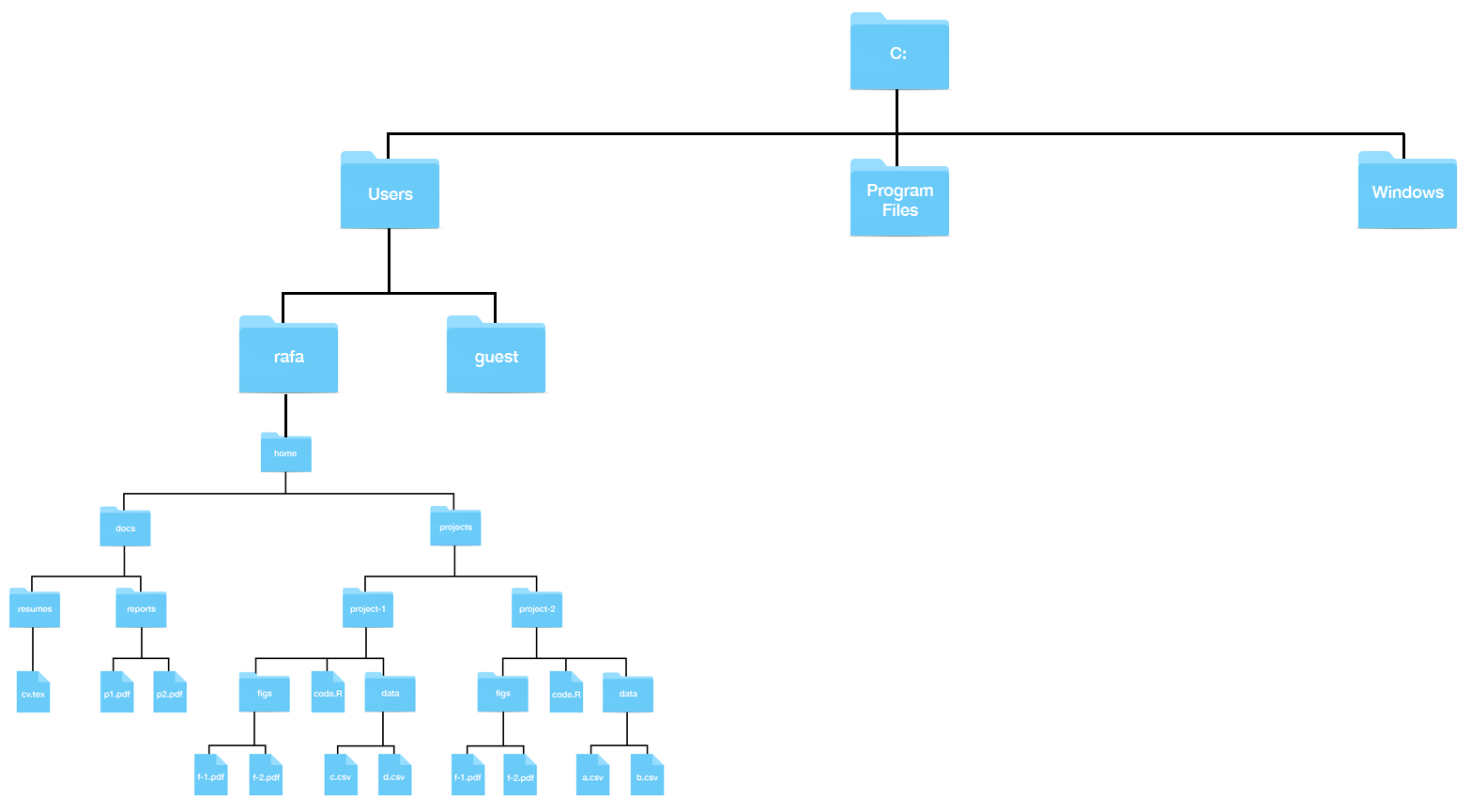

Now suppose you can’t see your home directory on your screen. You would somehow need to make it appear on your screen. One way to do this is to navigate from what is called the root directory all the way to your home directory. Any filesystem will have what is called a root directory, which is the directory that contains all directories. The home directory shown in the figure above will usually be two or more levels from the root. On Windows, you will have a structure like this:

while on the Mac, it will be like this:

On Windows, the typical R installation will make your Documents directory your home directory in R. This will likely be different from your home directory in Git Bash. Generally, when we discuss home directories, we refer to the Unix home directory which for Windows, in this book, is the Git Bash Unix directory.

18.3.3 Working directory

The concept of a current location is part of the point-and-click experience: at any given moment we are in a folder and see the content of that folder. As you search for a file, as we did above, you are experiencing the concept of a current location: once you double click on a directory, you change locations and are now in that folder, as opposed to the folder you were in before.

In Unix, we don’t have the same visual cues, but the concept of a current location is indispensable. We refer to this as the working directory. Each terminal window you have open has a working directory associated with it.

How do we know what is our working directory? To answer this, we learn our next Unix command: pwd, which stands for print working directory. This command returns the working directory.

Open a terminal and type:

pwdWe do not show the result of running this command because it will be quite different on your system compared to others. If you open a terminal and type pwd as your first command, you should see something like /Users/yourusername on a Mac or something like /c/Users/yourusername on Windows. The character string returned by calling pwd represents your working directory. When we first open a terminal, it will start in our home directory so in this case the working directory is the home directory.

Notice that the forward slashes / in the strings above separate directories. So, for example, the location /c/Users/rafa implies that our working directory is called rafa and it is a subdirectory of Users, which is a subdirectory of c, which is a subdirectory of the root directory. The root directory is therefore represented by just a forward slash: /.

18.3.4 Paths

We refer to the string returned by pwd as the full path of the working directory. The name comes from the fact that this string spells out the path you need to follow to get to the directory in question from the root directory. Every directory has a full path. Later, we will about relative paths, which tell us how to get to a directory from the working directory.

In Unix, we use the shorthand ~ as a nickname for your home directory. So, for example, if docs is a directory in your home directory, the full path for docs can be written like this ~/docs.

Most terminals will show the path to your working directory right on the command line. If you are using default settings and open a terminal on the Mac, you will see that right at the command line you have something like computername:~ username with ~ representing your working directory, which in this example is the home directory ~. The same is true for the Git Bash terminal where you will see something like username@computername MINGW64 ~, with the working directory at the end. When we change directories, we will see this change on both Macs and Windows.

18.4 Unix commands

We will now learn a series of Unix commands that will permit us to prepare a directory for a data science project. We also provide examples of commands that, if you type into your terminal, will return an error. This is because we are assuming the filesystem in the earlier diagram. Your filesystem is different. In the next section, we will provide examples that you can type in.

18.4.1 ls: Listing directory content

In a point-and-click system, we know what is in a directory because we see it. In the terminal, we do not see the icons. Instead, we use the command ls to list the directory content.

To see the content of your home directory, open a terminal and type:

lsWe will see more examples soon.

18.4.2 mkdir and rmdir: make and remove a directory

When we are preparing for a data science project, we will need to create directories. In Unix, we can do this with the command mkdir, which stands for make directory.

Because you will soon be working on several projects, we highly recommend creating a directory called projects in your home directory.

You can try this particular example on your system. Open a terminal and type:

mkdir projectsIf you do this correctly, nothing will happen: no news is good news. If the directory already exists, you will get an error message and the existing directory will remain untouched.

To confirm that you created the directory, you can list the contents of the current working directory:

lsYou should see the directory we just created listed. Perhaps you can also see many other directories that were already on your computer.

For illustrative purposes, let’s make a few more directories. You can list more than one directory name like this:

mkdir docs teachingYou can check to see if the three directories were created:

lsIf you made a mistake and need to remove the directory, you can use the command rmdir to remove it.

mkdir junk

rmdir junkThis will remove the directory as long as it is empty. If it is not empty, you will get an error message and the directory will remain untouched. To remove directories that are not empty, we will learn about the command rm later.

18.4.4 Examples

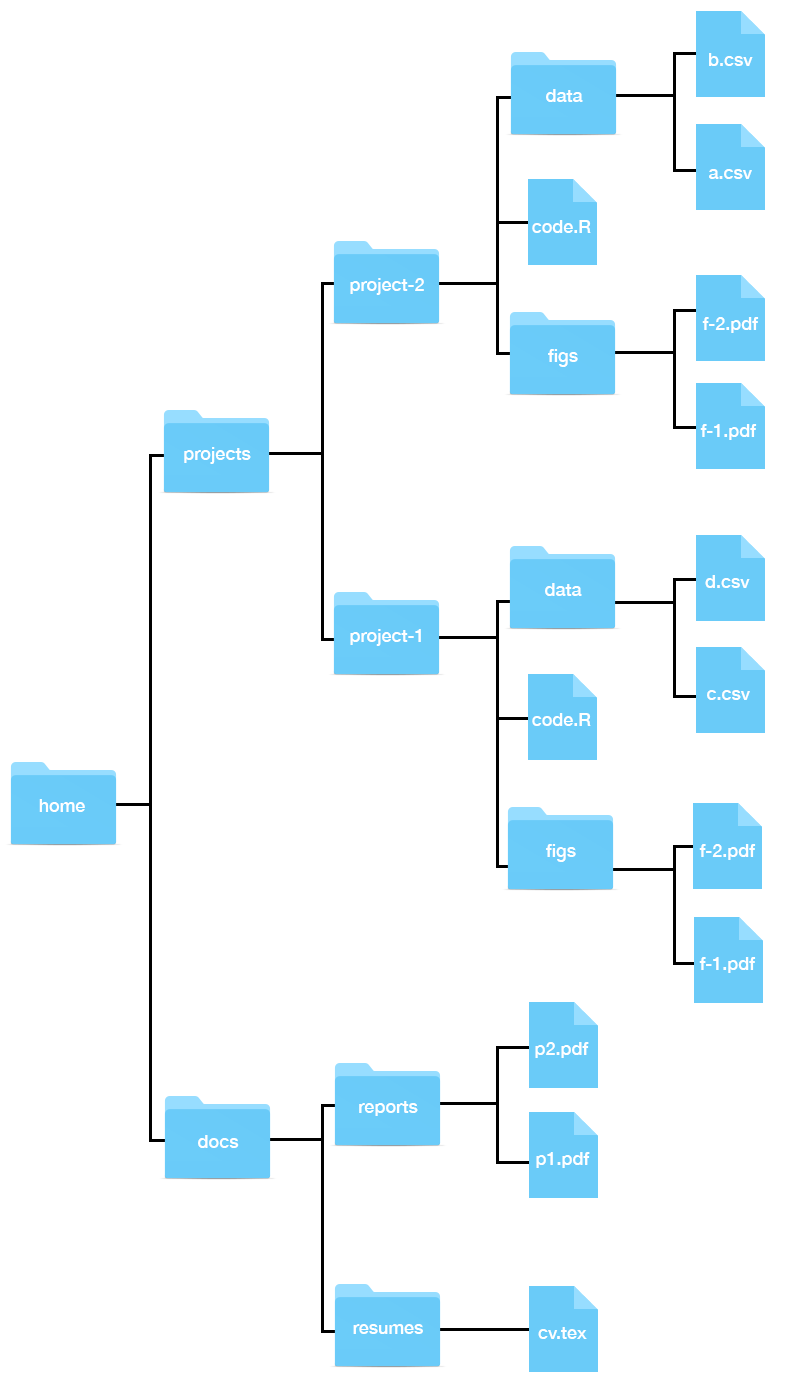

Let’s explore some examples of using cd. To help visualize, we will show the graphical representation of our filesystem vertically:

Suppose our working directory is ~/projects and we want to move to figs in project-1.

Here it is convenient to use relative paths:

cd project-1/figsNow suppose our working directory is ~/projects and we want to move to reports in docs, how can we do this?

One way is to use relative paths:

cd ../docs/reportsAnother is to use the full path:

cd ~/docs/reportsIf you are trying this out on your system, remember to use auto-complete.

Let’s examine one more example. Suppose we are in ~/projects/project-1/figs and want to change to ~/projects/project-2. Again, there are two ways.

With relative paths:

cd ../../project-2and with full paths:

cd ~/projects/project-218.5 More Unix commands

18.5.1 mv: moving files

In a point-and-click system, we move files from one directory to another by dragging and dropping. In Unix, we use the mv command.

mv will not ask “are you sure?” if your move results in overwriting a file.

Now that you know how to use full and relative paths, using mv is relatively straightforward. The general form is:

mv path-to-file path-to-destination-directoryFor example, if we want to move the file cv.tex from resumes to reports, you could use the full paths like this:

mv ~/docs/resumes/cv.tex ~/docs/reports/You can also use relative paths. You could do this:

cd ~/docs/resumes

mv cv.tex ../reports/or this:

cd ~/docs/reports/

mv ../resumes/cv.tex ./Notice that in the last one we used the working directory shortcut . to give a relative path as the destination directory.

We can also use mv to change the name of a file. To do this, instead of the second argument being the destination directory, it also includes a filename. So, for example, to change the name from cv.tex to resume.tex, we simply type:

cd ~/docs/resumes

mv cv.tex resume.texWe can also combine the move and a rename. For example:

cd ~/docs/resumes

mv cv.tex ../reports/resume.texAnd we can move entire directories. To move the resumes directory into reports, we do as follows:

mv ~/docs/resumes ~/docs/reports/It is important to add the last / to make it clear you do not want to rename the resumes directory to reports, but rather move it into the reports directory.

18.5.2 cp: copying files

The command cp behaves similar to mv except instead of moving, we copy the file, meaning that the original file stays untouched.

So in all the mv examples above, you can switch mv to cp and they will copy instead of move with one exception: we can’t copy entire directories without learning about arguments, which we do later.

18.5.3 rm: removing files

In point-and-click systems, we remove files by dragging and dropping them into the trash or using a special click on the mouse. In Unix, we use the rm command.

Unlike throwing files into the trash, rm is permanent. Be careful!

The general way it works is as follows:

rm filenameYou can actually list files as well like this:

rm filename-1 filename-2 filename-3You can use full or relative paths. To remove non-empty directories, you will have to learn about arguments, which we do later.

18.5.4 less: looking at a file

Often you want to quickly look at the content of a file. If this file is a text file, the quickest way to do is by using the command less. To look a the file cv.tex, you do this:

cd ~/docs/resumes

less cv.tex To exit the viewer, you type q. If the files are long, you can use the arrow keys to move up and down. There are many other keyboard commands you can use within less to, for example, search or jump pages.

If you are wondering why the command is called less, it is because the original was called more, as in “show me more of this file”. The second version was called less because of the saying “less is more”.

18.6 Case study: Preparing for a project

We are now ready to prepare a directory for a project. We will use the US murders project9 as an example.

You should start by creating a directory where you will keep all your projects. We recommend a directory called projects in your home directory. To do this you would type:

cd ~

mkdir projectsOur project relates to gun violence murders so we will call the directory for our project murders. It will be a subdirectory in our projects directories. In the murders directory, we will create two subdirectories to hold the raw data and intermediate data. We will call these data and rda, respectively.

Open a terminal and make sure you are in the home directory:

cd ~Now run the following commands to create the directory structure we want. At the end, we use ls and pwd to confirm we have generated the correct directories in the correct working directory:

cd projects

mkdir murders

cd murders

mkdir data rdas

ls

pwdNote that the full path of our murders dataset is ~/projects/murders.

So if we open a new terminal and want to navigate into that directory we type:

cd projects/murdersIn Section 20.3 we will describe how we can use RStudio to organize a data analysis project, once these directories have been created.

18.7 Advanced Unix

Most Unix implementations include a large number of powerful tools and utilities. We have just learned the very basics here. We recommend that you use Unix as your main file management tool. It will take time to become comfortable with it, but as you struggle, you will find yourself learning just by looking up solutions on the internet. In this section, we superficially cover slightly more advanced topics. The main purpose of the section is to make you aware of what is available rather than explain everything in detail.

18.7.1 Arguments

Most Unix commands can be run with arguments. Arguments are typically defined by using a dash - or two dashes -- (depending on the command) followed by a letter or a word. An example of an argument is the -r behind rm. The r stands for recursive, and the result is that files and directories are removed recursively, which means that if you type:

rm -r directory-nameall files, subdirectories, files in subdirectories, subdirectories in subdirectories, and so on, will be removed. This is equivalent to throwing a folder in the trash, except you can’t recover it. Once you remove it, it is deleted for good. Often, when you are removing directories, you will encounter files that are protected. In such cases, you can use the argument -f which stands for force.

You can also combine arguments. For instance, to remove a directory regardless of protected files, you type:

rm -rf directory-nameRemember that once you remove there is no going back, so use this command very carefully.

A command that is often called with argument is ls. Here are some examples:

ls -a The a stands for all. This argument makes ls show you all files in the directory, including hidden files. In Unix, all files starting with a . are hidden. Many applications create hidden directories to store important information without getting in the way of your work. An example is git (which we cover in depth in Chapter 19). Once you initialize a directory as a git directory with git init, a hidden directory called .git is created. Another hidden file is the .gitignore file.

Another example of using an argument is:

ls -l The l stands for long and the result is that more information about the files is shown.

It is often useful to see files in chronological order. For that we use:

ls -t and to reverse the order of how files are shown you can use:

ls -r We can combine all these arguments to show more information for all files in reverse chronological order:

ls -lart Each command has a different set of arguments. In the next section, we learn how to find out what they each do.

18.7.2 Getting help

As you may have noticed, Unix uses an extreme version of abbreviations. This makes it very efficient, but hard to guess how to call commands. To make up for this weakness, Unix includes complete help files or man pages (man is short for manual). In most systems, you can type man followed by the command name to get help. So for ls, we would type:

man lsThis command is not available in some of the compact implementations of Unix, such as Git Bash. An alternative way to get help that works on Git Bash is to type the command followed by --help. So for ls, it would be as follows:

ls --help18.7.3 Pipes

The help pages are typically long and if you type the commands above to see the help, it scrolls all the way to the end. It would be useful if we could save the help to a file and then use less to see it. The pipe, written like this |, does something similar. It pipes the results of a command to the command after the pipe. This is similar to the pipe |> that we use in R. To get more help we thus can type:

man ls | lessor in Git Bash:

ls --help | less This is also useful when listing files with many files. We can type:

ls -lart | less 18.7.4 Wild cards

Some of the most powerful aspects of Unix are the wild cards. Suppose we want to remove all the temporary html files produced while trouble shooting for a project. Imagine there are dozens of files. It would be quite painful to remove them one by one. In Unix, we can actually write an expression that means all the files that end in .html. To do this we type wild card: *. As discussed in the data wrangling part of this book, this character means any number of any combination of characters. Specifically, to list all html files, we would type:

ls *.htmlTo remove all html files in a directory, we would type:

The other useful wild card is the ? symbol. This means any single character. So if all the files we want to erase have the form file-001.html with the numbers going from 1 to 999, we can type:

rm file-???.htmlThis will only remove files with that format.

We can combine wild cards. For example, to remove all files with the form file-001 up to file-999 regardless of suffix, we can type:

rm file-???.* Combining rm with the * wild card can be dangerous. There are combinations of these commands that will erase your entire filesystem without asking “are you sure?”. So make sure you understand how it works before using this wild card with the rm command. We recommend always checking what files will match the wild card first by using the ls command.

18.7.5 Environment variables

Unix has settings that affect your command line environment. These are called environment variables. The home directory is one of them. We can actually change some of these. In Unix, variables are distinguished from other entities by adding a $ in front. The home directory is stored in $HOME.

Earlier we saw that echo is the Unix command for print. So we can see our home directory by typing:

echo $HOME You can see them all by typing:

envYou can change some of these environment variables. But their names vary across different shells. We describe shells in the next section.

18.7.6 Shells

Much of what we use in this chapter is part of what is called the Unix shell. There are actually different shells, but the differences are almost unnoticeable. They are also important, although we do not cover those here. You can see what shell you are using by typing:

echo $SHELLThe most common one is bash.

Once you know the shell, you can change environmental variables. In Bash Shell, we do it using export variable value. To change the path, described in more detail soon, you would type:

export PATH = /usr/bin/Don’t actually run this command though!

There is a program that is run before each terminal starts where you can edit variables so they change whenever you call the terminal. This changes in different implementations, but if using bash, you can create a file called .bashrc, .bash_profile,.bash_login, or .profile. You might already have one.

18.7.7 Executables

In Unix, all programs are files. They are called executables. So ls, mv and git are all files. But where are these program files? You can find out using the command which:

which git

#> /usr/bin/gitThat directory is probably full of program files. The directory /usr/bin usually holds many program files. If you type:

ls /usr/binin your terminal, you will see several executable files.

There are other directories that usually hold program files. The Application directory in the Mac or Program Files directory in Windows are examples.

When you type ls, Unix knows to run a program which is an executable that is stored in some other directory. So how does Unix know where to find it? This information is included in the environmental variable $PATH. If you type:

echo $PATHyou will see a list of directories separated by :. The directory /usr/bin is probably one of the first ones on the list.

Unix looks for program files in those directories in that order. Although we don’t teach it here, you can actually create executables yourself. However, if you put it in your working directory and this directory is not on the path, you can’t run it just by typing the command. You get around this by typing the full path. So if your command is called my-ls, you can type:

./my-lsOnce you have mastered the basics of Unix, you should consider learning to write your own executables as they can help alleviate repetitive work.

18.7.8 Permissions and file types

If you type:

ls -lAt the beginning, you will see a series of symbols like this -rw-r--r--. This string indicates the type of file: regular file -, directory d, or executable x. This string also indicates the permission of the file: is it readable? writable? executable? Can other users on the system read the file? Can other users on the system edit the file? Can other users execute if the file is executable? This is more advanced than what we cover here, but you can learn much more in a Unix reference book.

18.7.9 Commands you should learn

There are many commands that we do not teach in this book, but we want to make you aware of them and what they do. They are:

open/start - On the Mac,

open filenametries to figure out the right application of the filename and open it with that application. This is a very useful command. On Git Bash, you can trystart filename. Try opening anRorRmdfile withopenorstart: it should open them with RStudio.nano - Opens a bare-bones text editor.

tar - Archives files and subdirectories of a directory into one file.

ssh - Connects to another computer.

find - Finds files by filename on your system.

grep - Searches for patterns in a file.

awk/sed - These are two very powerful commands that permit you to find specific strings in files and change them.

ln - Creates a symbolic link. We do not recommend its use, but you should be familiar with it.

18.7.10 File manipulation in R

We can also perform file management from within R. The key functions to learn about can be seen by looking at the help file for ?files10. Another useful function is unlink.

Although not generally recommended, you can run Unix commands in R using system.

https://www.edx.org/course/introduction-linux-linuxfoundationx-lfs101x-1↩︎

https://www.quora.com/Which-are-the-best-Unix-Linux-reference-books↩︎

https://jvns.ca/blog/2018/08/05/new-zine--bite-size-command-line/↩︎

https://library.si.edu/sites/default/files/tutorial/pdf/filenamingorganizing20180227.pdf↩︎