| Poll | Date | Sample | MoE | Clinton | Trump | Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP Average | 10/31 - 11/7 | -- | -- | 47.2 | 44.3 | Clinton +2.9 |

| Bloomberg | 11/4 - 11/6 | 799 LV | 3.5 | 46.0 | 43.0 | Clinton +3 |

| Economist | 11/4 - 11/7 | 3669 LV | -- | 49.0 | 45.0 | Clinton +4 |

| IBD | 11/3 - 11/6 | 1026 LV | 3.1 | 43.0 | 42.0 | Clinton +1 |

| ABC | 11/3 - 11/6 | 2220 LV | 2.5 | 49.0 | 46.0 | Clinton +3 |

| FOX News | 11/3 - 11/6 | 1295 LV | 2.5 | 48.0 | 44.0 | Clinton +4 |

| Monmouth | 11/3 - 11/6 | 748 LV | 3.6 | 50.0 | 44.0 | Clinton +6 |

| CBS News | 11/2 - 11/6 | 1426 LV | 3.0 | 47.0 | 43.0 | Clinton +4 |

| LA Times | 10/31 - 11/6 | 2935 LV | 4.5 | 43.0 | 48.0 | Trump +5 |

| NBC News | 11/3 - 11/5 | 1282 LV | 2.7 | 48.0 | 43.0 | Clinton +5 |

| NBC News | 10/31 - 11/6 | 30145 LV | 1.0 | 51.0 | 44.0 | Clinton +7 |

| McClatchy | 11/1 - 11/3 | 940 LV | 3.2 | 46.0 | 44.0 | Clinton +2 |

| Reuters | 10/31 - 11/4 | 2244 LV | 2.2 | 44.0 | 40.0 | Clinton +4 |

| GravisGravis | 10/31 - 10/31 | 5360 RV | 1.3 | 50.0 | 50.0 | Tie |

6 Parameters and Estimates

Opinion polling has been conducted since the 19th century. The general aim is to describe the opinions held by a specific population on a given set of topics. In recent times, these polls have been pervasive in the US during presidential elections. Polls are useful when interviewing every member of a specific population is logistically impossible. The general strategy involves interviewing a smaller, randomly chosen group and then inferring the opinions of the entire population from those of this subset. Statistical theory, known as inference, is used to justify the process and is the primary focus of this part of the book.

Perhaps the best known opinion polls are those conducted to determine which candidate is preferred by voters in a given election. Political strategists extensively use polls to decide, among other things, where to allocate resources, such as determining the geographical locations to focus their “get out the vote” efforts.

Elections are a particularly interesting instances of opinion polls because reveal the actual opinion of the entire population on election day. Of course, it costs millions of dollars to run an real election, which makes polling a cost-effective strategy for those seeking to forecast the results. In addition to strategist, news organizations are also interested in forecasting elections due to the apparent demand for what they reveal.

6.1 The sampling model for polls

We start by connecting probability theory to the task of using polls to learn about a population.

Although typically the results of polls run by political candidates are kept private, polls are also conducted by news organizations because results tend to be of interest to the general public and made public. We will eventually be looking at these public datasets.

Real Clear Politics1 is an example of a news aggregator that organizes and publishes poll results. For example, they present the following poll results, reporting estimates of the popular vote for the 2016 presidential election2:

Let’s make some observations about the table above. First, observe that different polls, all conducted days before the election, report different spreads: the estimated difference between support for the two candidates. Notice that the reported spreads hover around what eventually became the actual result: Clinton won the popular vote by 2.1%. Additionally, we o see a column titled MoE which stands for margin of error.

To help us understand the connection between polls and what we have learned, let’s construct a situation similar to what pollsters face. To simulate the challenge pollsters encounter in terms of competing with other pollsters for media attention, we will use an urn filled with beads to represent voters, and pretend we are competing for a $25 dollar prize. The challenge is to guess the spread between the proportion of blue and red beads in this urn (in this case, a pickle jar):

Before making a prediction, you can take a sample (with replacement) from the urn. To reflect the fact that running polls is expensive, it costs you $0.10 for each bead you sample. Therefore, if your sample size is 250, and you win, you will break even since you would have paid $25 to collect your $25 prize. Your entry into the competition can be an interval. If the interval you submit contains the true proportion, you receive half what you paid and proceed to the second phase of the competition. In the second phase, the entry with the smallest interval is selected as the winner.

The dslabs package includes a function that shows a random draw from this urn:

Think about how you would construct your interval based on the data shown above.

We have just described a simple sampling model for opinion polls. In this model, the beads inside the urn represent individuals who will vote on election day. The red beads represent those voting for the Republican candidate, while the blue beads represent the Democrats. For simplicity, let’s assume there are no other colors;that is, that there are just two parties: Republican and Democratic.

6.2 Populations, samples, parameters, and estimates

We want to predict the proportion of blue beads in the urn. Let’s call this quantity \(p\), which then tells us the proportion of red beads \(1-p\), and the spread \(p - (1-p)\), which simplifies to \(2p - 1\).

In statistical textbooks, the beads in the urn are called the population. The proportion of blue beads in the population \(p\) is called a parameter. The 25 beads we see in the previous plot are called a sample. The goal of statistical inference is to predict the parameter \(p\) based on the observed data in the sample.

Can we do this with the 25 observations above? It is certainly informative. For example, given that we see 13 red and 12 blue beads, it is unlikely that \(p\) > .9 or \(p\) < .1. But are we ready to predict with certainty that there are more red beads than blue in the jar?

We want to construct an estimate of \(p\) using only the information we observe. An estimate should be thought of as a summary of the observed data that we think is informative about the parameter of interest. It seems intuitive to think that the proportion of blue beads in the sample \(0.48\) must be at least related to the actual proportion \(p\). But do we simply predict \(p\) to be 0.48? First, remember that the sample proportion is a random variable. If we run the command take_poll(25) four times, we get a different answer each time, since the sample proportion is a random variable.

Observe that in the four random samples shown above, the sample proportions range from 0.44 to 0.60. By describing the distribution of this random variable, we will be able to gain insights into how good this estimate is and how we can improve it.

6.2.1 The sample average

Conducting an opinion poll is being modeled as taking a random sample from an urn. We propose using the proportion of blue beads in our sample as an estimate of the parameter \(p\). Once we have this estimate, we can easily report an estimate for the spread \(2p-1\). However, for simplicity, we will illustrate the concepts for estimating \(p\). We will use our knowledge of probability to justify our use of the sample proportion and to quantify its proximity to the population proportion \(p\).

We start by defining the random variable \(X\) as \(X=1\), if we pick a blue bead at random, and \(X=0\) if it is red. This implies that the population is a list of 0s and 1s. If we sample \(N\) beads, then the average of the draws \(X_1, \dots, X_N\) is equivalent to the proportion of blue beads in our sample. This is because adding the \(X\)s is equivalent to counting the blue beads, and dividing this count by the total \(N\) is equivalent to computing a proportion. We use the symbol \(\bar{X}\) to represent this average. In statistics textbooks, a bar on top of a symbol typically denotes the average. The theory we just covered about the sum of draws becomes useful because the average is a sum of draws multiplied by the constant \(1/N\):

\[\bar{X} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N X_i\]

For simplicity, let’s assume that the draws are independent; after we see each sampled bead, we return it to the urn. In this case, what do we know about the distribution of the sum of draws? Firstly, we know that the expected value of the sum of draws is \(N\) times the average of the values in the urn. We know that the average of the 0s and 1s in the urn must be \(p\), the proportion of blue beads.

Here, we encounter an important difference compared to what we did in the section on probability: we don’t know the composition of the urn. While we know there are blue and red beads, we don’t know how many of each. This is what we want to find out: we are trying to estimate \(p\).

6.2.2 Parameters

Just as we use variables to define unknowns in systems of equations, in statistical inference, we define parameters to represent unknown parts of our models. In the urn model, which we are using to simulate an opinion poll, we do not know the proportion of blue beads in the urn. We define the parameters \(p\) to represent this quantity. Since our main goal is determining \(p\), we are going to estimate this parameter.

Introductory statistics textbooks usually use the population average as the first example of a parameter. Note that in our example the parameter of interest \(p\) is defined by the proportion of 1s (blue) and 0s (red) in the urn, which is also the average of the numbers in the urn. Our parameter of interest can therefore be thought of as a population average.

The concepts presented here on how we estimate parameters, and provide insights into how good these estimates are, extend to many data analysis tasks. For example, we may want to determine the difference in health improvement between patients receiving treatment and a control group, investigate the health effects of smoking on a population, analyze the differences in racial groups of fatal shootings by police, or assess the rate of change in life expectancy in the US during the last 10 years. All these questions can be framed as a task of estimating a parameter from a sample.

6.3 Polling versus forecasting

Before we continue, it’s important to clarify a practical issue related to forecasting an election. If a poll is conducted four months before the election, it is estimating the \(p\) for that moment, and not for election day. The \(p\) for election night might be different, as people’s opinions tend to fluctuate through time. Generally, the polls conducted the night before the election tend to be the most accurate, since opinions do not change significantly in a day. However, forecasters try to develop tools that model how opinions vary over time and aim to predict the election night results by taking into consideration these fluctuations. We will explore some approaches for doing this in a later section.

6.4 Properties of our estimate: expected value and standard error

To understand how good our estimate is, we will describe the statistical properties of the random variable defined above: the sample proportion \(\bar{X}\). Remember that \(\bar{X}\) is the sum of independent draws so the rules we covered in the probability chapter apply.

Applying the concepts we have learned, the expected value of the sum \(N\bar{X}\) is \(N \times\) the average of the urn, denoted as \(p\). Dividing by the non-random constant \(N\) yields the expected value of the average \(\bar{X}\) as \(p\). We can write it using our mathematical notation:

\[ \mbox{E}(\bar{X}) = p \]

We can also use what we learned to determine the standard error: the standard error of the sum is \(\sqrt{N} \times\) the standard deviation of the urn. Can we compute the standard error of the urn? We learned a formula that tells us it is \((1-0) \sqrt{p (1-p)}\) = \(\sqrt{p (1-p)}\). Because we are dividing the sum by \(N\), we arrive at the following formula for the standard error of the average:

\[ \mbox{SE}(\bar{X}) = \sqrt{p(1-p)/N} \]

This result reveals the power of polls. The expected value of the sample proportion \(\bar{X}\) is the parameter of interest \(p\), and we can make the standard error as small as we want by increasing \(N\). The law of large numbers tells us that with a large enough poll, our estimate converges to \(p\).

If we take a large enough poll to make our standard error about 1%, we will be quite certain about who will win. But how large does the poll have to be for the standard error to be this small?

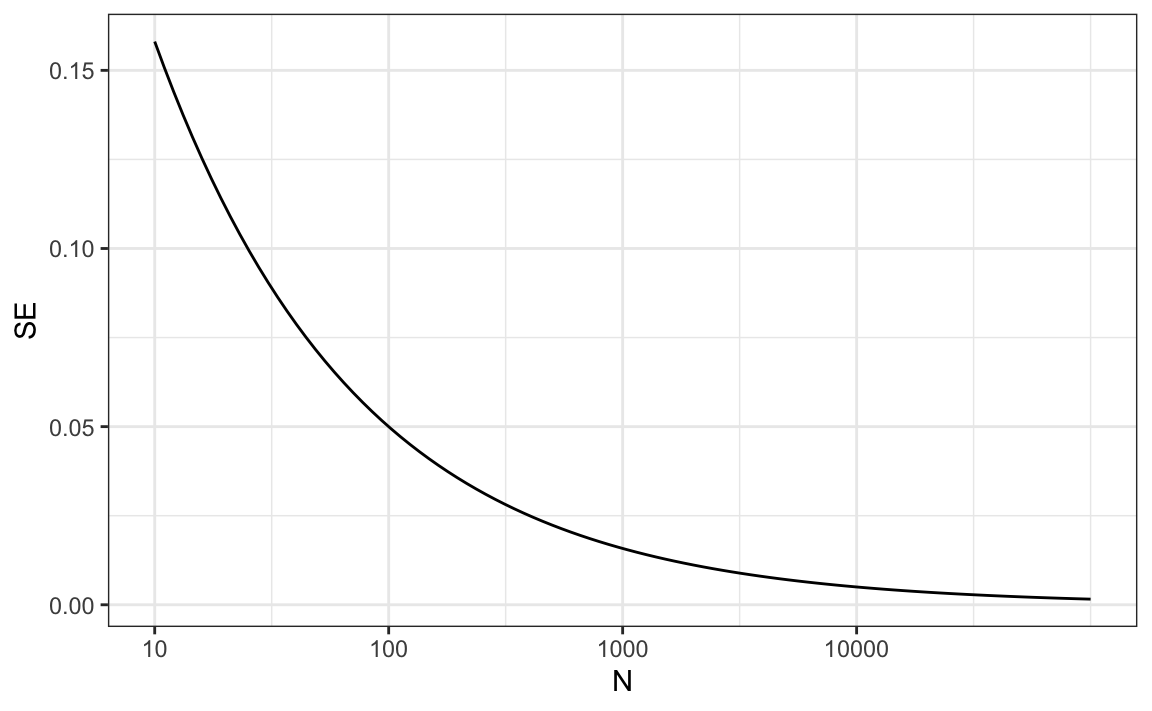

One problem is that we do not know \(p\), so we can’t compute the standard error. However, for illustrative purposes, let’s assume that \(p=0.51\) and make a plot of the standard error versus the sample size \(N\):

The plot shows that we would need a poll of over 10,000 people to achieve a standard error that low. We rarely see polls of this size due in part to the associated costs. According to the Real Clear Politics table, sample sizes in opinion polls range from 500-3,500 people. For a sample size of 1,000 and \(p=0.51\), the standard error is:

or 1.5 percentage points. So even with large polls, for close elections, \(\bar{X}\) can lead us astray if we don’t realize it is a random variable. Nonetheless, we can actually say more about how close we get the \(p\) and we do that in Chapter 7.

6.5 Exercises

1. Suppose you poll a population in which a proportion \(p\) of voters are Democrats and \(1-p\) are Republicans. Your sample size is \(N=25\). Consider the random variable \(S\), which is the total number of Democrats in your sample. What is the expected value of this random variable? Hint: It’s a function of \(p\).

2. What is the standard error of \(S\) ? Hint: It’s a function of \(p\).

3. Consider the random variable \(S/N\). This is equivalent to the sample average, which we have been denoting as \(\bar{X}\). What is the expected value of the \(\bar{X}\)? Hint: It’s a function of \(p\).

4. What is the standard error of \(\bar{X}\)? Hint: It’s a function of \(p\).

5. Write a line of code that gives you the standard error se for the problem above for several values of \(p\), specifically for p <- seq(0, 1, length = 100). Make a plot of se versus p.

6. Copy the code above and put it inside a for-loop to make the plot for \(N=25\), \(N=100\), and \(N=1000\).

7. If we are interested in the difference in proportions, \(\mu = p - (1-p)\), our estimate is \(\hat{\mu} = \bar{X} - (1-\bar{X})\). Use the rules we learned about sums of random variables and scaled random variables to derive the expected value of \(\hat{\mu}\).

8. What is the standard error of \(\hat{\mu}\)?

9. If the actual \(p=.45\), it means the Republicans are winning by a relatively large margin, since \(\mu = -.1\), which is a 10% margin of victory. In this case, what is the standard error of \(2\hat{X}-1\) if we take a sample of \(N=25\)?

10. Given the answer to exercise 9, which of the following best describes your strategy of using a sample size of \(N=25\)?

- The expected value of our estimate \(2\bar{X}-1\) is \(\mu\), so our prediction will be accurate.

- Our standard error is larger than the difference, so the chances of \(2\bar{X}-1\) representing a large margin are not small. We should pick a larger sample size.

- The difference is 10% and the standard error is about 0.2, therefore much smaller than the difference.

- Because we don’t know \(p\), we have no way of knowing that making \(N\) larger would actually improve our standard error.