29 Resampling and Model Assessment

In this chapter, we introduce resampling, one of the most important ideas in machine learning. Here we focus on the conceptual and mathematical aspects. We will describe how to implement resampling methods in practice with the caret package later in Section 31.2. To motivate the concept, we will use the two predictor digits data presented in Section 28.3.1 and introduce k-nearest neighbors (kNN), to demonstrate the ideas.

29.1 Motivation with k-nearest neighbors

We are interested in estimating the conditional probability function:

\[ p(\mathbf{x}) = \mathrm{Pr}(Y = 1 \mid X_1 = x_1 , X_2 = x_2). \]

as defined in Section 28.5.

With k-nearest neighbors (kNN) we estimate \(p(\mathbf{x})\) in a similar way to bin smoothing. First, we define the distance between all observations based on the features. Then, for any point \(\mathbf{x}_0\), we estimate \(p(\mathbf{x}_0)\) by identifying the \(k\) nearest points to \(\mathbf{x}_0\) and taking an average of the \(y\)s associated with these points. We refer to the set of points used to compute the average as the neighborhood.

Due to the connection we described earlier between conditional expectations and conditional probabilities, this gives us \(\hat{p}(\mathbf{x}_0)\), just like the bin smoother gave us an estimate of a trend. As with bin smoothers, we can control the flexibility of our estimate through a parameter, in the case the number o neighbors \(k\): larger \(k\)s result in smoother estimates, while smaller \(k\)s result in more flexible and wiggly estimates.

To fit a \(k\)-nearest neighbors model, we use the knn3 function from the caret package. The help file shows two ways to call this function; we will use the formula interface, which lets us write the model in the form

outcome ~ predictor_1 + predictor_2 + ...Because our training set is stored in a data frame, we can use the shorthand y ~ . to mean “use y as the outcome and all other columns as predictors.”

We must also choose the number of neighbors \(k\). The default is k = 5, which we will use here. Putting this together, our call looks like:

In this case, since our dataset is balanced and we care just as much about sensitivity as we do about specificity, we will use accuracy to quantify performance.

The predict function for knn3 returns estimes of \(p(\mathbf{x})\) (type = "prob") or the prediction (type = "class"):

y_hat_knn <- predict(knn_fit, mnist_27$test, type = "class")We see that kNN, with the default parameter, already beats GLM:

mean(y_hat_knn == mnist_27$test$y)

#> [1] 0.815To see why this is the case, we plot \(\hat{p}(\mathbf{x})\) and compare it to the true conditional probability \(p(\mathbf{x})\):

We see that kNN adapts better to the non-linear shape of \(p(\mathbf{x})\). However, our estimate has some islands of blue in the red area, which intuitively does not make much sense. We notice that we have higher accuracy in the train set compared to the test set:

This is due to what we call over-training.

29.2 Over-training

With kNN, over-training is at its worst when we set \(k = 1\). With \(k = 1\), the estimate for each \(\mathbf{x}\) in the training set is obtained with just the \(y\) corresponding to that point. In this case, if the \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are unique, we will obtain perfect accuracy in the training set because each point is used to predict itself (if the predictors are not unique and have different outcomes for at least one set of predictors, then it is impossible to predict perfectly).

Here we fit a kNN model with \(k = 1\) and confirm we get near perfect accuracy in the training set:

But in the test set, accuracy is actually worse than what we obtained with regression:

We can see the over-fitting problem by plotting the decision rule boundaries produced by \(\hat{p}(\mathbf{x})\):

The estimate \(\hat{p}(\mathbf{x})\) follows the training data too closely (left). You can see that, in the training set, boundaries have been drawn to perfectly surround a single red point in a sea of blue. Because most points \(\mathbf{x}\) are unique, the prediction is either 1 or 0 and the prediction for that point is the associated label. However, once we introduce the test set (right), we see that many of these small islands now have the opposite color and we end up making several incorrect predictions.

29.3 Over-smoothing

Although not as badly as with \(k=1\), we saw that with \(k = 5\) we also over-trained. Hence, we should consider a larger \(k\). Let’s try, as an example, a much larger number: \(k = 401\).

The estimate turns out to be similar to the one obtained with regression:

In this case, \(k\) is so large that it does not permit enough flexibility. We call this over-smoothing.

29.4 Tuning parameters

It is very common for machine learning algorithms to require that we set one or more values before fitting the model. A simple example is the choice of \(k\) in k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN). In Chapter 30, we will see additional examples. These values are referred to as tuning parameters, and an important part of applying machine learning in practice is choosing them, often called tuning the model.

So how do we pick tuning parameters? For instance, how do we decide on the best \(k\) in kNN? In principle, we want the value of \(k\) that maximizes accuracy or, equivalently, minimizes the expected MSE as defined in Section 27.8. The challenge is that we do not know the true expected error. The goal of resampling methods is to estimate this error for any given algorithm and set of tuning parameters, such as \(k\).

To see why we need resampling, let’s repeat what we did earlier: compare training and test set accuracy, but now for a range of \(k\) values. We can then plot the accuracy estimates for each choice of \(k\):

First, note that the estimate obtained from the training set is generally more optimistic, higher accuracy, than the estimate from the test set, with the gap being larger for smaller values of \(k\). This is a classic symptom of overfitting.

Should we simply choose the value of \(k\) that gives the highest accuracy on the test set and report its accuracy? This approach has two important drawbacks:

The accuracy–versus–(k) curve is noisy. We do not expect small changes in \(k\) to cause large changes in accuracy or MSE. The jagged pattern occurs because each accuracy estimate is based on a finite test sample, so it fluctuates due to random variation. As a result, the “best” \(k\) may appear best just by chance.

We are using the test set twice. Although we are not fitting the model on the test set, we are using it to choose \(k\) and then using it again to report accuracy. This leads to an optimistic estimate of performance that will typically not hold up on truly new data.

Resampling methods provide a principled solution to both problems by reducing variability and ensuring that test data are not used twice, once for evaluation and again for tuning.

29.5 Mathematical description of resampling methods

In Section 29.1 we introduced \(k\)-nearest neighbors (kNN) as a simple example to motivate this chapter. In that setting, the algorithm depends on only one tuning parameter, \(k\), which directly affects performance. More generally, machine learning algorithms often involve multiple tuning parameters. Here we use the notation \(\lambda\) to represent the full set of parameters that define the algorithm.

To keep track of how these choices affect performance, we write the predictions produced by a given parameter set for observation \(i\) as \(\hat{y}_i(\lambda)\) and the corresponding mean squared error as \(\mathrm{MSE}(\lambda)\). Our goal is to find the value of \(\lambda\) that minimizes \(\mathrm{MSE}(\lambda)\).

Resampling methods provide practical ways to estimate \(\mathrm{MSE}(\lambda)\) and therefore guide us toward the best tuning parameters.

An intuitive first attempt is the apparent error defined in Section 27.8 and used in the previous section:

\[ \hat{\mbox{MSE}}(\lambda) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i = 1}^N \left\{\hat{y}_i(\lambda) - y_i\right\}^2 \]

As noted in the previous section, this estimate is a random variable, based on just one test set, with enough variability to affect the choice of the best \(\lambda\) substantially.

Now imagine a world in which we could obtain data repeatedly, say from new random samples. We could take a very large number \(B\) of new samples, split each of them into training and test sets, and define:

\[ \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=1}^B \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N \left\{\hat{y}_i^b(\lambda) - y_i^b\right\}^2 \]

with \(y_i^b\) the \(i\)th observation in test sample \(b\) and \(\hat{y}_{i}^b(\lambda)\) the prediction obtained with the algorithm defined by parameter \(\lambda\) and trained on train set \(b\). The law of large numbers tells us that as \(B\) becomes larger, this quantity gets closer and closer to \(\mbox{MSE}(\lambda)\). This is of course a theoretical consideration as we rarely get access to more than one dataset for algorithm development, but the concept inspires resampling methods.

The general idea behind resampling methods is to generate a series of different random samples from the data at hand. There are several approaches to doing this, but all randomly generate several smaller datasets that are not used for training, and instead are used to estimate MSE. Next, we describe cross validation, one of the most widely used resampling methods.

29.6 Cross validation

Overall, we are provided a dataset (blue) and we need to build an algorithm, using this dataset, that will eventually be used in completely independent datasets (yellow) that we might not even see.

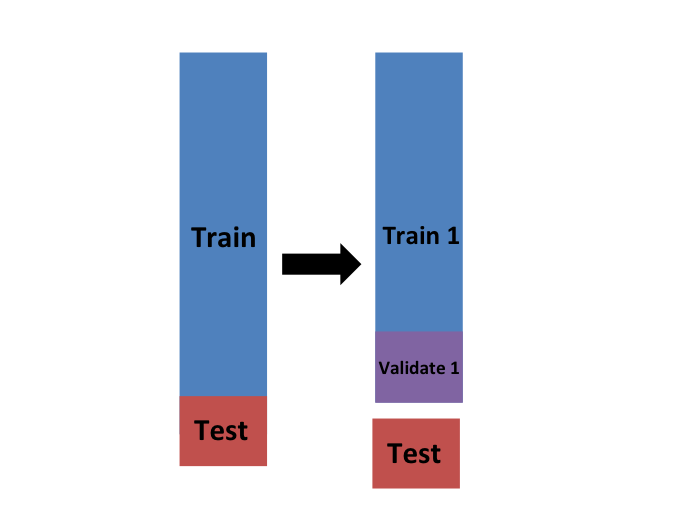

So to imitate this situation, we start by carving out a piece of our dataset and pretend it is an independent dataset: we divide the dataset into a training set (blue) and a test set (red). We will train the entirety of our algorithm, including the choice of parameter \(\lambda\), exclusively on the training set and use the test set only for evaluation purposes.

We usually try to select a small piece of the dataset so that we have as much data as possible to train. However, we also want the test set to be large so that we obtain a stable estimate of the MSE without fitting an impractical number of models. Typical choices are to use 10%-20% of the data for testing.

Let’s reiterate that it is indispensable that we not use the test set at all: not for filtering out rows, not for selecting features, not for anything!

But then how do we optimize \(\lambda\)? In cross validation, we achieve this by splitting the training set into two: the training and validation sets.

We will do this many times assuring that the estimates of MSE obtained in each dataset are independent from each other. There are several proposed methods for doing this. Here we describe one of these approaches, K-fold cross validation, in detail to provide the general idea used in all approaches.

K-fold cross validation

As a reminder, we are going to imitate the concept used when introducing this version of the MSE:

\[ \mbox{MSE}(\lambda) \approx\frac{1}{B} \sum_{b = 1}^B \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i = 1}^N \left(\hat{y}_i^b(\lambda) - y_i^b\right)^2 \]

We want to generate a dataset that can be thought of as independent random sample, and do this \(B\) times. The K in K-fold cross validation, represents the number of time \(B\). In the illustrations below we show an example that uses \(B = 5\).

We will eventually end up with \(B\) samples, but let’s start by describing how to construct the first: we simply pick \(M = N/B\) observations at random (we round if \(M\) is not a round number) and think of these as a random sample \(y_1^b, \dots, y_M^b\), with \(b = 1\). We call this the validation set.

Now we can fit the model in the training set, then compute the apparent error on the independent set:

\[ \hat{\mbox{MSE}}_b(\lambda) = \frac{1}{M}\sum_{i = 1}^M \left(\hat{y}_i^b(\lambda) - y_i^b\right)^2 \]

As a reminder, this is just one sample and will therefore return a noisy estimate of the true error. In K-fold cross validation, we randomly split the observations into \(B\) non-overlapping sets:

Now we repeat the calculation above for each of these sets \(b = 1,\dots,B\) and obtain \(\hat{\mbox{MSE}}_1(\lambda),\dots, \hat{\mbox{MSE}}_B(\lambda)\). Then, for our final estimate, we compute the average:

\[ \hat{\mbox{MSE}}(\lambda) = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b = 1}^B \hat{\mbox{MSE}}_b(\lambda) \]

and obtain an estimate of our loss. A final step would be to select the \(\lambda\) that minimizes the MSE.

How many folds?

Now how do we pick the cross validation fold? Large values of \(B\) are preferable because the training data better imitates the original dataset. However, larger values of \(B\) will have much slower computation time: for example, 100-fold cross validation will be 10 times slower than 10-fold cross validation. For this reason, the choices of \(B = 5\) and \(B = 10\) are popular.

Estimate MSE of our optimized algorithm

We have described how to use cross validation to optimize parameters. However, we now have to take into account the fact that the optimization occurred on the training data and we therefore need an estimate of our final algorithm based on data that was not used to optimize the choice. Here is where we use the test set we separated early on:

We can actually do cross validation again, say five times:

and obtain a final estimate of our expected loss by averaging the five MSE estimates. However, note that last cross validation iteration means that our entire compute time gets multiplied by the number of repetitions. You will soon learn that fitting each algorithm takes time because we are performing many complex computations. As a result, we are always looking for ways to reduce this time. For the final evaluation, we often just use the one test set.

Once we are satisfied with this model and want to make it available to others, we could refit the model on the entire dataset, without changing the optimized parameters.

29.7 Boostrap resampling

Typically, cross-validation involves partitioning the original dataset into a training set to train the model and a testing set to evaluate it. With the bootstrap approach, based on the ideas described in Chapter 14, you can create multiple different training datasets via bootstrapping. This method is sometimes called bootstrap aggregating or bagging.

In bootstrap resampling, we create a large number of bootstrap samples from the original training dataset. Each bootstrap sample is created by randomly selecting observations with replacement, usually the same size as the original training dataset. For each bootstrap sample, we fit the model and compute the MSE estimate on the observations not selected in the random sampling, referred to as the out-of-bag observations. These out-of-bag observations serve a similar role to a validation set in standard cross-validation.

We then average the MSEs obtained in the out-of-bag observations from each bootstrap sample to estimate the model’s performance.

This approach is actually the default approach in the caret package. We describe how to implement resampling methods with the caret package in Chapter 31.

29.8 Comparison of MSE estimates

In Section 29.1, we computed an estimate of MSE based just on the provided test set (shown in red in the plot below). Here we show how the cross-validation techniques described above help reduce variability. The green curve below shows the results of applying K-fold cross validation with 10 folds, leaving out 10% of the data for validation. We can see that the variance is reduced substantially. The blue curve is the result of using 100 bootstrap samples to estimate MSE. The variability is reduced even further, but at the cost of a 10 fold increase in computation time.

Note that the three resampling approaches lead to different choices of \(\lambda\). Using the accuracy curves:

- The naive approach selects \(\lambda =\) 9.

- The 10-fold cross-validation approach selects \(\lambda =\) 55.

- The bootstrap approach selects \(\lambda =\) 65.

These differences highlight an important point: your choice of \(\lambda\) is only as good as your estimate of the test error. Reliable resampling methods are essential for finding a tuning parameter that truly generalizes well.

29.9 Exercises

Below is a cleaner, clearer, student-friendly version of the exercise set, expanded to a total of 10 exercises, with tightened wording, improved motivation, and careful explanations of what students are expected to do.

I also added one more exercise (now Exercise 7) so that the set flows logically and reaches 10 total.

30 Exercises: Overfitting, Feature Selection, and Resampling

We will work with a dataset in which the predictors and the outcome are entirely unrelated. This setting helps us understand how misleading results can arise when we accidentally “peek” at the test set or use the full dataset to perform feature selection.

Generate the dataset:

Because x and y are independent, no classifier should achieve an accuracy much larger than 0.5.

1. Using only x_subset, randomly split the data into 80% training and 20% test.

Fit a logistic regression model (glm, family = “binomial”) on the training set and compute the test-set accuracy.

Repeat this entire procedure five times with new random splits and report the average test accuracy.

2. We now pick predictors using t-tests, even though all predictors are noise. For each column of x, compute a t-test comparing values in the y = 1 group to y = 0, and extract p-values:

Create an index ind with the predictors whose p-values are < 0.01. How many predictors survive this cutoff?

3. Define:

x_subset <- x[, ind]Repeat Exercise 1 but using this new x_subset.

What is the average test accuracy now? Is it above 0.5?

4. Why is accuracy > 0.5 if the data are independent?

Choose the best explanation:

- The function

trainestimates accuracy on the same data used to train the model. - We are over-fitting because the model uses 100 predictors.

- We used the entire dataset to perform feature selection, but cross-validation was done after selecting predictors.

- High accuracy is simply random variation.

5. Redo the analysis, but this time perform feature selection within each resampling split.

This means:

- For each fold or resample,

- select predictors using only the training portion,

- fit the model using those selected predictors,

- evaluate on the corresponding test/validation portion.

You should now obtain an accuracy close to 0.5. Explain why.

6. Load the tissue_gene_expression dataset.

Split the data:

- 80% training

- 20% test

Then, within the training set, repeatedly split into:

- 90% training

- 10% validation

Use these validation splits to choose the best k for a kNN classifier (using train).

Report the value of k that performs best.

7. Using the best k found in Exercise 6, retrain the kNN model on the entire training set, and evaluate its accuracy on the held-out test set.

Is the accuracy much worse, much better, or roughly the same as what you observed on the validation sets? Explain why this comparison matters.

8. We can create bootstrap samples using createResample.

set.seed(1995)

indexes <- createResample(mnist_27$train$y, 10)In the first bootstrap sample, how many times do the indices 3, 4, and 7 appear?

9. Repeat the previous exercise for all 10 bootstrap samples.

Which indices never appear at all in each sample? How many observations on average get omitted?

10. Explain in your own words why a bootstrap sample (sampling with replacement):

- must include some observations multiple times,

- must omit others entirely, and

- is still considered a valid “resampled dataset.”

Relate this explanation to the idea of using bootstrap samples to estimate prediction error.